Labyrinth (Gr. λαβύρινθος, Lat. labyrinthus), the name given by the Greeks and Romans to buildings, entirely or partly subterranean, containing a number of chambers and intricate passages, which rendered egress puzzling and difficult. The word is considered by some to be of Egyptian origin, while others connect it with the Gr. λαῦρα, the passage of a mine. Another derivation suggested is from λάβρυς, a Lydian or Carian word meaning a “double-edged axe” (Journal of Hellenic Studies, xxi. 109, 268), according to which the Cretan labyrinth or palace of Minos was the house of the double axe, the symbol of Zeus.

Pliny (Nat. Hist. xxxvi. 19, 91) mentions the following as the four famous labyrinths of antiquity.

1. The Egyptian: of which a description is given by Herodotus (ii. 148) and Strabo (xvii. 811). It was situated to the east of Lake Moeris, opposite the ancient site of Arsinoë or Crocodilopolis. According to Egyptologists, the word means “the temple at the entrance of the lake.” According to Herodotus, the entire building, surrounded by a single wall, contained twelve courts and 3000 chambers, 1500 above and 1500 below ground. The roofs were wholly of stone, and the walls covered with sculpture. On one side stood a pyramid 40 orgyiae, or about 243 ft. high. Herodotus himself went through the upper chambers, but was not permitted to visit those underground, which he was told contained the tombs of the kings who had built the labyrinth, and of the sacred crocodiles. Other ancient authorities considered that it was built as a place of meeting for the Egyptian nomes or political divisions; but it is more likely that it was intended for sepulchral purposes. It was the work of Amenemhē III., of the 12th dynasty, who lived about 2300 B.C. It was first located by the Egyptologist Lepsius to the north of Hawara in the Fayum, and (in 1888) Flinders Petrie discovered its foundation, the extent of which is about 1000 ft. long by 800 ft. wide. Immediately to the north of it is the pyramid of Hawara, in which the mummies of the king and his daughter have been found (see W. M. Flinders Petrie, Hawara, Biahmu, and Arsinoë, 1889).

2. The Cretan: said to have been built by Daedalus on the plan of the Egyptian, and famous for its connexion with the legend of the Minotaur. It is doubtful whether it ever had any real existence and Diodorus Siculus says that in his time it had already disappeared. By the older writers it was placed near Cnossus, and is represented on coins of that city, but nothing corresponding to it has been found during the course of the recent excavations, unless the royal palace was meant. The rocks of Crete are full of winding caves, which gave the first idea of the legendary labyrinth. Later writers (for instance, Claudian, De sexto Cons. Honorii, 634) place it near Gortyna, and a set of winding passages and chambers close to that place is still pointed out as the labyrinth; these are, however, in reality ancient quarries.

3. The Lemnian: similar in construction to the Egyptian. Remains of it existed in the time of Pliny. Its chief feature was its 150 columns.

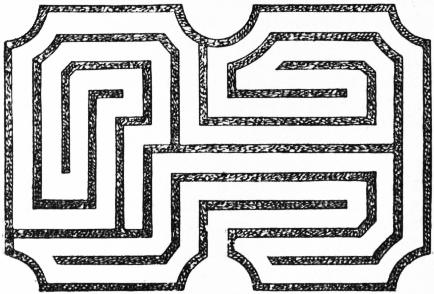

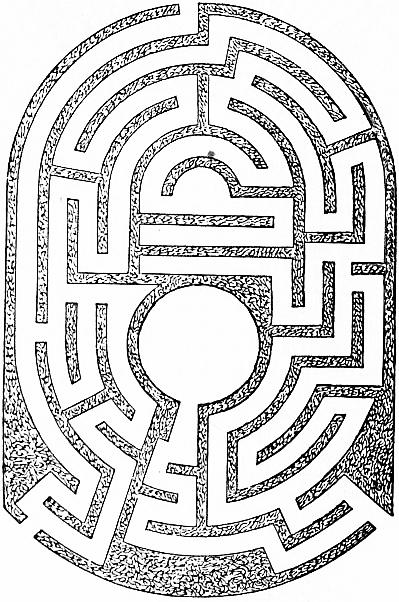

|

| Fig. 1.—Labyrinth of London and Wise. |

4. The Italian: a series of chambers in the lower part of the tomb of Porsena at Clusium. This tomb was 300 ft. square and 50 ft. high, and underneath it was a labyrinth, from which it was exceedingly difficult to find an exit without the assistance of a clew of thread. It has been maintained that this tomb is to be recognized in the mound named Poggio Gajella near Chiusi.

Lastly, Pliny (xxxvi. 19) applies the word to a rude drawing on the ground or pavement, to some extent anticipating the modern or garden maze.

On the Egyptian labyrinth see A. Wiedemann, Ägyptische Geschichte (1884), p. 258, and his edition of the second book of Herodotus (1890); on the Cretan, C. Höck, Kreta (1823-1829), and A. J. Evans in Journal of Hellenic Studies; on the subject generally, articles in Roscher’s Lexikon der Mythologie and Daremberg and Saglio’s Dictionnaire des antiquités.

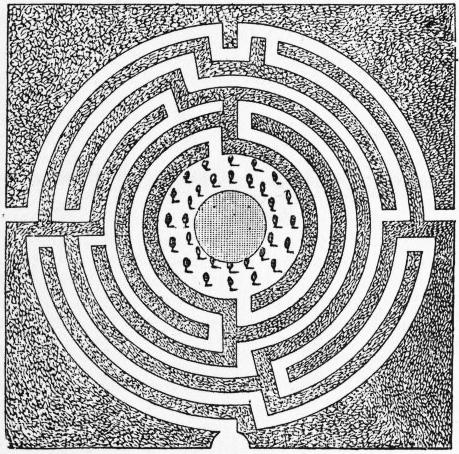

|

| Fig. 2.—Labyrinth of Batty Langley. |

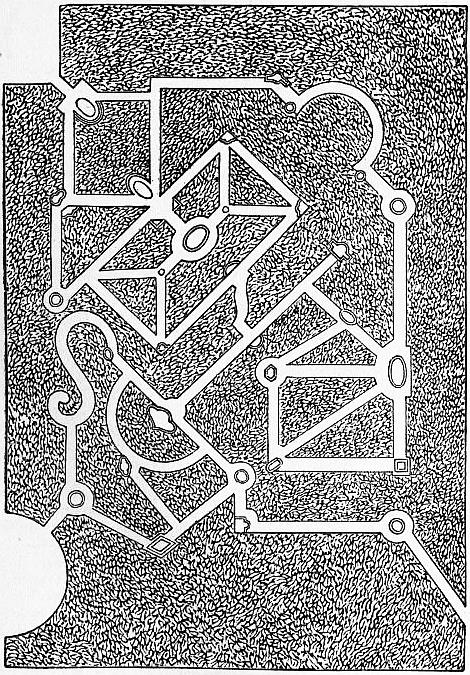

|

| Fig. 3.—Labyrinth at Versailles. |

In gardening, a labyrinth or maze means an intricate network of pathways enclosed by hedges or plantations, so that those who enter become bewildered in their efforts to find the centre or make their exit. It is a remnant of the old geometrical style of gardening. There are two methods of forming it. That which is perhaps the more common consists of walks, or alleys as they were formerly called, laid out and kept to an equal width or nearly so by parallel hedges, which should be so close and thick that the eye cannot readily penetrate them. The task is to get to the centre, which is often raised, and generally contains a covered seat, a fountain, a statue or even a small group of trees. After reaching this point the next thing is to return to the entrance, when it is found that egress is as difficult as ingress. To every design of this sort there should be a key, but even those who know the key are apt to be perplexed. Sometimes the design consists of alleys only, as in fig. 1, published in 1706 by London and Wise. In such a case, when the farther end is reached, there only remains to travel back again. Of a more pretentious character was a design published by Switzer in 1742. This is of octagonal form, with very numerous parallel hedges and paths, and “six different entrances, whereof there is but one that leads to the centre, and that is attended with some difficulties and a great many stops.” Some of the older designs for labyrinths, however, avoid this close parallelism of the alleys, which, though equally involved and intricate in their windings, are carried through blocks of thick planting, as shown in fig. 2, from a design published in 1728 by Batty Langley. These blocks of shrubbery have been called wildernesses. To this latter class belongs the celebrated labyrinth at Versailles (fig. 3), of which Switzer observes, that it “is allowed by all to be the noblest of its kind in the world.”

|

| Fig. 4.—Maze at Hampton Court. |

|

| Fig. 5.—Maze at Somerleyton Hall. |

Whatever style be adopted, it is essential that there should be a thick healthy growth of the hedges or shrubberies that confine the wanderer. The trees used should be impenetrable to the eye, and so tall that no one can look over them; and the paths should be of gravel and well kept. The trees chiefly used for the hedges, and the best for the purpose, are the hornbeam among deciduous trees, or the yew among evergreens. The beech might be used instead of the hornbeam on suitable soil. The green holly might be planted as an evergreen with very good results, and so might the American arbor vitae if the natural soil presented no obstacle. The ground must be well prepared, so as to give the trees a good start, and a mulching of manure during the early years of their growth would be of much advantage. They must be kept trimmed in or clipped, especially in their earlier stages; trimming with the knife is much to be preferred to clipping with shears. Any plants getting much in advance of the rest should be topped, and the whole kept to some 4 ft. or 5 ft. in height until the lower parts are well thickened, when it may be allowed to acquire the allotted height by moderate annual increments. In cutting, the hedge (as indeed all hedges) should be kept broadest at the base and narrowed upwards, which prevents it from getting thin and bare below by the stronger growth being drawn to the tops.

The maze in the gardens at Hampton Court Palace (fig. 4) is considered one of the finest examples in England. It was planted in the early part of the reign of William III., though it has been supposed that a maze had existed there since the time of Henry VIII. It is constructed on the hedge and alley system, and was, it is believed, originally planted with hornbeam, but many of the plants have been replaced by hollies, yews, &c., so that the vegetation is mixed. The walks are about half a mile in length, and the ground occupied is a little over a quarter of an acre. The centre contains two large trees, with a seat beneath each. The key to reach this resting place is to keep the right hand continuously in contact with the hedge from first to last, going round all the stops.

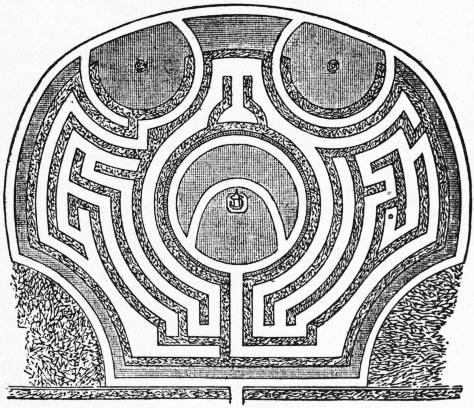

|

| Fig. 6.—Labyrinth in Horticultural Society’s Garden. |

The maze in the gardens at Somerleyton Hall, near Lowestoft (fig. 5), was designed by Mr John Thomas. The hedges are of English yew, are about 6½ ft. high, and have been planted about sixty years. In the centre is a grass mound, raised to the height of the hedges, and on this mound is a pagoda, approached by a curved grass path. At the two corners on the western side are banks of laurels 15 or 16 ft. high. On each side of the hedges throughout the labyrinth is a small strip of grass.

There was also a labyrinth at Theobald’s Park, near Cheshunt, when this place passed from the earl of Salisbury into the possession of James I. Another is said to have existed at Wimbledon House, the seat of Earl Spencer, which was probably laid out by Brown in the 18th century. There is an interesting labyrinth, somewhat after the plan of fig. 2, at Mistley Place, Manningtree.

When the gardens of the Royal Horticultural Society at South Kensington were being planned, Albert, Prince Consort, the president of the society, especially desired that there should be a maze formed in the ante-garden, which was made in the form shown in fig. 6. This labyrinth, designed by Lieut. W. A. Nesfield, was for many years the chief point of attraction to the younger visitors to the gardens; but it was allowed to go to ruin, and had to be destroyed. The gardens themselves are now built over.