Gettysburg, a borough and the county-seat of Adams county, Pennsylvania, U.S.A., about 35 m. S.W. of Harrisburg. Pop. (1900) 3495; (1910) 4030. It is served by the Western Maryland and the Gettysburg & Harrisburg railways. The site of the borough is a valley about 1½ m. wide; the neighbouring country abounds in attractive scenery. Katalysine Spring in the vicinity was once a well-known summer resort; its waters contain lithia in solution. Gettysburg has several small manufacturing establishments and is the seat of Pennsylvania College (opened in 1832, and the oldest Lutheran college in America), which had 312 students (68 in the preparatory department) in 1907-1908, and of a Lutheran theological seminary, opened in 1826 on Seminary Ridge; but the borough is best known as the scene of one of the most important battles of the Civil War. Very soon after the battle a soldiers’ national cemetery was laid out here, in which the bodies of about 3600 Union soldiers have been buried; and at the dedication of this cemetery, in November 1863, President Lincoln delivered his celebrated “Gettysburg Address.” In 1864 the Gettysburg Battle-Field Memorial Association was incorporated, and the work of this association resulted in the conversion of the battle-field into a National Park, an act for the purpose being passed by Congress in 1895. Within the park the lines of battle have been carefully marked, and about 600 monuments, 1000 markers, and 500 iron tablets have been erected by states and regimental associations. Hundreds of cannon have been mounted, and five observation towers have been built. From 1816 to 1840 Gettysburg was the home of Thaddeus Stevens. Gettysburg was settled about 1740, was laid out in 1787, was made the county-seat in 1800, and was incorporated as a borough in 1806.

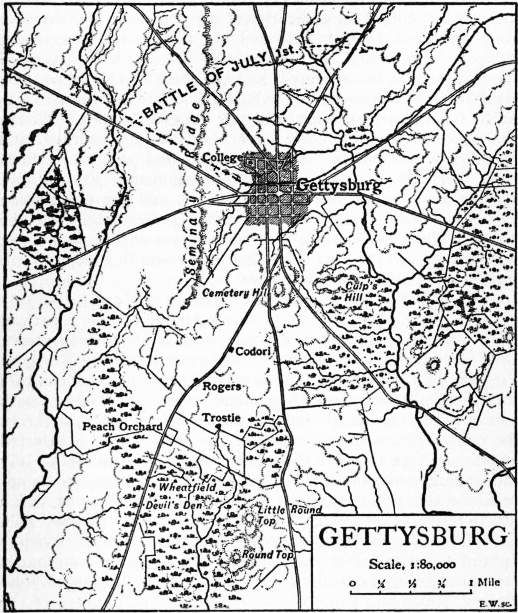

Battle of Gettysburg.—The battle of the 1st, 2nd and 3rd of July 1863 is often regarded as the turning-point of the American Civil War (q.v.) although it arose from a chance encounter. Lee, the commander of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, had merely ordered his scattered forces to concentrate there, while Meade, the Federal commander, held the town with a cavalry division, supported by two weak army corps, to screen the concentration of his Army of the Potomac in a selected position on Pipe Creek to the south-eastward. On the 1st of July the leading troops of General A. P. Hill’s Confederate corps approached Gettysburg from the west to meet Ewell’s corps, which was to the N. of the town, whilst Longstreet’s corps followed Hill. Lee’s intention was to close up Hill, Longstreet and Ewell before fighting a battle. But Hill’s leading brigades met a strenuous resistance from the Federal cavalry division of General John Buford, which was promptly supported by the infantry of the I. corps under General J. F. Reynolds. The Federals so far held their own that Hill had to deploy two-thirds of his corps for action, and the western approaches of Gettysburg were still held when Ewell appeared to the northward. Reynolds had already fallen, and the command of the Federals, after being held for a time by Gen. Abner Doubleday, was taken over by Gen. O. O. Howard, the commander of the XI. corps, which took post to bar the way to Ewell on the north side. But Ewell’s attack, led by the fiery Jubal Early, swiftly drove back the XI. corps to Gettysburg; the I. corps, with its flank thus laid open, fell back also, and the remnants of both Federal corps retreated through Gettysburg to the Cemetery Hill position. They had lost severely in the struggle against superior numbers, and there had been some disorder in the retreat. Still a formidable line of defence was taken up on Cemetery Hill and both Ewell and Lee refrained from further attacks, for the Confederates had also lost heavily during the day and their concentration was not complete. In the meanwhile Meade had sent forward General W. S. Hancock, the commander of the Federal II. corps, to examine the state of affairs, and on Hancock’s report he decided to fight on the Cemetery Hill position. Two corps of his army were still distant, but the XII. arrived before night, the III. was near, and Hancock moved the II. corps on his own initiative. Headquarters and the artillery reserve started for Gettysburg on the night of the 1st. On the other side, the last divisions of Hill’s and Ewell’s corps formed up opposite the new Federal position, and Longstreet’s corps prepared to attack its left.

Owing, however, to misunderstandings between Lee and Longstreet (q.v.), the Confederates did not attack early on the morning of the 2nd, so that Meade’s army had plenty of time to make its dispositions. The Federal line at this time occupied the horse-shoe ridge, the right of which was formed by Culp’s Hill, and the centre by the Cemetery hill, whence the left wing stretched southward, the III. corps on the left, however, being thrown forward considerably. The XII. held Culp’s, the remnant of the I. and XI. the Cemetery hills. On the left was the II., and in its advanced position—the famous “Salient”—the III., soon to be supported by the V.; the VI., with the reserve artillery, formed the general reserve. It was late in the day when the Confederate attack was made, and valuable time had been lost, but Longstreet’s troops advanced with great spirit. The III. corps Salient was the scene of desperate fighting; and the “Peach Orchard” and the “Devil’s Den” became as famous as the “Bloody Angle” of Spottsylvania or the “Hornets’ Nest” of Shiloh. While the Confederate attack was developing, the important positions of Round Top and Little Round Top were unoccupied by the defenders—an omission which was repaired only in the nick of time by the commanding engineer of the army, General G. K. Warren, who hastily called up troops of the V. corps. The attack of a Confederate division was, after a hard struggle, repulsed, and the Federals retained possession of the Round Tops. The III. corps in the meantime, furiously attacked by troops of Hill’s and Longstreet’s corps, was steadily pressed back, and the Confederates actually penetrated the main line of the defenders, though for want of support the brigades which achieved this were quickly driven out. Ewell, on the Confederate left, waited for the sound of Longstreet’s guns, and thus no attack was made by him until late in the day. Here Culp’s Hill was carried with ease by one of Ewell’s divisions, most of the Federal XII. corps having been withdrawn to aid in the fight on the other wing; but Early’s division was repulsed in its efforts to storm Cemetery Hill, and the two divisions of the centre (one of Hill’s, one of Ewell’s corps) remained inactive.

That no decisive success had been obtained by Lee was clear to all, but Ewell’s men on Culp’s Hill, and Longstreet’s corps below Round Top, threatened to turn both flanks of the Federal position, which was no longer a compact horseshoe but had been considerably prolonged to the left; and many of the units in the Federal army had been severely handled in the two days’ fighting. Meade, however, after discussing the eventuality of a retreat with his corps commanders, made up his mind to hold his ground. Lee now decided to alter his tactics. The broken ground near Round Top offered so many obstacles that he decided not to press Longstreet’s attack further. Ewell was to resume his attack on Meade’s extreme right, while the decisive blow was to be given in the centre (between Cemetery Hill and Trostle’s) by an assault delivered in the Napoleonic manner by the fresh troops of Pickett’s division (Longstreet’s corps). Meade, however, was not disposed to resign Culp’s Hill, and with it the command of the Federal line of retreat, to Ewell, and at early dawn on the 3rd a division of the XII. corps, well supported by artillery, opened the Federal counter-attack; the Confederates made a strenuous resistance, but after four hours’ hard fighting the other division of the XII. corps, and a brigade of the VI., intervened with decisive effect, and the Confederates were driven off the hill. The defeat of Ewell did not, however, cause Lee to alter his plans. Pickett’s division was to lead in the great assault, supported by part of Hill’s corps (the latter, however, had already been engaged). Colonel E. P. Alexander, Longstreet’s chief of artillery, formed up one long line of seventy-five guns, and sixty-five guns of Hill’s corps came into action on his left. To the converging fire of these 140 guns the Federals, cramped for space, could only oppose seventy-seven. The attacking troops formed up before 9 A.M., yet it was long before Longstreet could bring himself to order the advance, upon which so much depended, and it was not till about 1 P.M. that the guns at last opened fire to prepare the grand attack. The Federal artillery promptly replied, but after thirty minutes’ cannonade its commander, Gen. H. J. Hunt, ordered his batteries to cease fire in order to reserve their ammunition to meet the infantry attack. Ten minutes later Pickett asked and received permission to advance, and the infantry moved forward to cross the 1800 yds. which separated them from the Federal line. Their own artillery was short of ammunition, the projectiles of that day were not sufficiently effective to cover the advance at long ranges, and thus the Confederates, as they came closer to the enemy, met a tremendous fire of unshaken infantry and artillery.

The charge of Pickett’s division is one of the most famous episodes of military history. In the teeth of an appalling fire from the rifles of the defending infantry, who were well sheltered, and from the guns which Hunt had reserved for the crisis, the Virginian regiments pressed on, and with a final effort broke Meade’s first line. But the strain was too great for the supporting brigades, and Pickett was left without assistance. Hancock made a fierce counterstroke, and the remnant of the Confederates retreated. Of Pickett’s own division over three-quarters, 3393 officers and men out of 4500, were left on the field, two of his three brigadiers were killed and the third wounded, and of fifteen regimental commanders ten were killed and five wounded. One regiment lost 90% of its numbers. The failure of this assault practically ended the battle; but Lee’s line was so formidable that Meade did not in his turn send forward the Army of the Potomac. By the morning of the 5th of July Lee’s army was in full retreat for Virginia. He had lost about 30,000 men in killed, wounded and missing out of a total force of perhaps 75,000. Meade’s losses were over 23,000 out of about 82,000 on the field. The main body of the cavalry on both sides was absent from the field, but a determined cavalry action was fought on the 3rd of July between the Confederate cavalry under J. E. B. Stuart and that of the Federals under D. McM. Gregg some miles E. of the battlefield, and other Federal cavalry made a dashing charge in the broken ground south-west of Round Top on the third day, inflicting thereby, though at great loss to themselves, a temporary check on the right wing of Longstreet’s infantry.