Flamingo (Port. Flamingo, Span. Flamenco), one of the tallest and most beautiful birds, conspicuous for the bright flame-coloured or scarlet patch upon its wings, and long known by its classical name Phoenicopterus, as an inhabitant of most of the countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea. Flamingos have a very wide distribution, and the sole genus comprises only a few species. Ph. roseus or antiquorum, white, with a rosy tinge above, and with scarlet wing-coverts, while the remiges are black (as in all species), ranges from the Cape Verde Islands to India and Ceylon, north as far as Lake Baikal; southwards through Africa and Madagascar, eventually as P. minor. P. ruber, entirely light vermilion, extends from Florida to Para and the Galapagos; P. chilensis s. ignipalliatus, from Peru to Patagonia, more resembles the classical species; while P. andinus, the tallest of all, which lacks the hallux, inhabits the salt lakes of the elevated desert of Atacama, whence it extends into Chile and Argentina. Fossil remains of flamingos have been described from the Lower Miocene of France as P. croizeti, and from the Pliocene of Oregon. From the Mid-Miocene to the Oligocene of France are known several species of Palaelodus, Elornis and Agnopterus, which have relatively shorter legs, longer toes and a complicated hypotarsus, and represent an earlier family, less specialized although not directly ancestral to the flamingos. Palaelodidae and Phoenicopteridae together form the larger group Phoenicopteri. These are in many respects exactly intermediate between Anserine and stork-like birds, so much so in fact that T.H. Huxley preferred to keep them separate as Amphimorphae. However, if we carefully sift their characters, the flamingos obviously reveal themselves as much nearer related to the Ciconiae, especially to Platalea and Ibis, than to the Anseres. This is the opinion arrived at by W.F.R. Weldon, M. Fuerbringer and Gadow, while others prefer the goose-like voice and the webbed toes as reliable characters. (For a detailed analysis of this instructive question see Bronn’s Thierreich, Aves Syst. p. 146.)

|

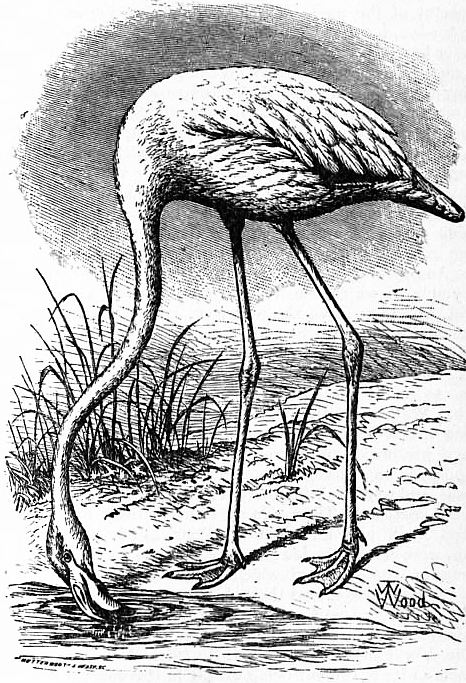

| The Flamingo. |

The food of the flamingo seems to consist chiefly of small aquatic invertebrate animals which live in the mud of lagoons, for instance Mollusca, but also of Confervae and other low salt-water algae. Whilst feeding, the bird wades about, stirs up the mud with its feet, and, reversing the ordinary position of its head so as to hold the crown downwards and to look backwards, sifts the mud through its bill. This is abruptly bent down in the middle, as if broken; the upper jaw is rather flat and narrow, while the lower jaw is very roomy and furnished with numerous lamellae, which, together with the thick and large tongue, act like a sieve, an arrangement enhanced by the considerable movability of the upper jaw. Then the bird erects its long neck to swallow the selected food. When flying, flamingos present a striking and beautiful sight, with legs and neck stretched out straight, looking like white and rosy or scarlet crosses with black arms. Not less fascinating is a flock of these sociable birds when at rest, standing on one or both legs, with their long necks twisted or coiled upon the body in any conceivable position.

The nest is likewise peculiar. It is built of mud, a somewhat conical structure rising above the water according to the depth, of which the cone is from a few inches to 2 ft. in height. If, as often happens, the water-level sinks, the nests stand out higher. On the top is a shallow cup for the reception of the one or two eggs, which have a bluish-white shell with chalky incrustation. Of course the hen sits with her legs doubled up under her, as does any other long-legged bird. It seems strange that many ornithologists should have given credence to W. Dampier’s statement of the mode of incubation (New Voyage round the World, ed. 2, i. p. 71, London, 1699): “And when they lay their eggs, or hatch them, they stand all the while, not on the hillock, but close by it with their legs on the ground and in the water, resting themselves against the hillock, and covering the hollow nest upon it with their rumps,” &c. P.S. Pallas (Zoograph. Rosso-Asiatica, ii. p. 208) tried to improve upon this by stating that the standing bird leans upon the nest with its breast! The young, which are hatched after about four weeks’ incubation, look very different from the adult. The small bill is still quite straight and the legs are short. The whole body is covered with a thick coat of short nestling feathers, pure white in colour. These neossoptiles or first feathers bear no resemblance to those of the Anseriform birds, but agree in detail with those of spoonbills, the young of which the little flamingos resemble to a striking extent, but they leave the nest soon after their birth to shift for themselves like ducks and geese.