Economic Entomology, the name given to the study of insects based on their relation to man, his domestic animals and his crops, and, in the case of those that are injurious, of the practical methods by which they can be prevented from doing harm, or be destroyed when present. In Great Britain little attention is paid to this important branch of agricultural science, but in America and the British colonies the case is different. Nearly every state in America has its official economic entomologists, and nearly every one of the British crown colonies is provided with one or more able men who help the agricultural community to battle against the insect pests. Most, if not all, of the important knowledge of remedies comes from America, where this subject reaches the highest perfection; even the life-histories of some of the British pests have been traced out in the United States and British colonies more completely than at home, from the creatures that have been introduced from Europe.

Some idea of the importance of this subject may be gained from the following figures. The estimated loss by the vine Phylloxera in the Gironde alone was £32,000,000; for all the French wine districts £100,000,000 would not cover the damage. It has been stated on good evidence that a loss of £7,000,000 per annum was caused by the attack of the ox warble fly on cattle in England alone. In a single season Aberdeenshire suffered nearly £90,000 worth of damage owing to the ravages of the diamond back moth on the root crops; in New York state the codling moth caused a loss of $3,000,000 to apple-growers. Yet these figures are nothing compared to the losses due to scale insects, locusts and other pests.

The most able exponent of this subject in Great Britain was John Curtis, whose treatise on Farm Insects, published in 1860, is still the standard British work dealing with the insect foes of corn, roots, grass and stored corn. The most important works dealing with fruit and other pests come from the pens of Saunders, Lintner, Riley, Slingerland and others in America and Canada, from Taschenberg, Lampa, Reuter and Kollar in Europe, and from French, Froggatt and Tryon in Australia. It was not until the last quarter of the 19th century that any real advance was made in the study of economic entomology. Among the early writings, besides the book of Curtis, there may also be mentioned a still useful little publication by Pohl and Kollar, entitled Insects Injurious to Gardeners, Foresters and Farmers, published in 1837, and Taschenberg’s Praktische Insecktenkunde. American literature began as far back as 1788, when a report on the Hessian fly was issued by Sir Joseph Banks; in 1817 Say began his writings; while in 1856 Asa Fitch started his report on the “Noxious Insects of New York.” Since that date the literature has largely increased. Among the most important reports, &c., may be mentioned those of C.V. Riley, published by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, extending from 1878 to his death, in which is embodied an enormous amount of valuable matter. At his death the work fell to Professor L.O. Howard, who constantly issues brochures of equal value in the form of Bulletins of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. The chief writings of J.A. Lintner extend from 1882 to 1898, in yearly parts, under the title of Reports on the Injurious Insects of the State of New York. Another author whose writings rank high on this subject is M.V. Slingerland, whose investigations are published by Cornell University. Among other Americans who have largely increased the literature and knowledge must be mentioned F.M. Webster and E.P. Felt. In 1883 appeared a work on fruit pests by William Saunders, which mainly applies to the American continent; and another small book on the same subject was published in 1898 by Miss Ormerod, dealing with the British pests. In Australia Tryon published a work on the Insect and Fungus Enemies of Queensland in 1889. Many other papers and reports are being issued from Australia, notably by Froggatt in New South Wales. At the Cape excellent works and papers are prepared and issued by the government entomologist, Dr Lounsbury, under the auspices of the Agricultural Department; while from India we have Cotes’s Notes on Economic Entomology, published by the Indian Museum in 1888, and other works, especially on tea pests.

Injurious insects occur among the following orders: Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Lepidoptera, Diptera, Hemiptera (both heteroptera and homoptera), Orthoptera, Neuroptera and Thysanoptera. The order Aptera also contains a few injurious species.

|

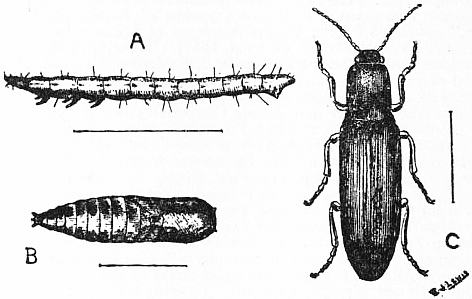

| Fig. 1.—A, Wireworm; B, pupa of Click Beetle; C, adult Click Beetle (Agriotes lineatum). |

Among the Coleoptera or beetles there is a group of world-wide pests, the Elateridae or click beetles, the adults of the various “wireworms.” The insects in the larval or wireworm stage attack the roots of plants, eating them away below the ground. The eggs deposited by the beetle in the ground develop into yellowish-brown wire-like grubs with six legs on the first three segments and a ventral prominence on the anal segment. The life of these subterranean pests differs in the various species; some undoubtedly (Agriotes lineatum) live for three or four years, during the greater part of which time they gnaw away at the roots of plants, carrying wholesale destruction before them. When mature they pass deep into the ground and pupate, appearing after a few months as the click beetles (fig. 1). Most crops are attacked by them, but they are particularly destructive to wheat and other cereals. With such subterranean pests little can be done beyond rolling the land to keep it firm, and thus preventing them from moving rapidly from plant to plant. A few crops, such as mustard, seem deleterious to them. By growing mustard and ploughing it in green the ground is made obnoxious to the wireworms, and may even be cleared of them. For root-feeders, bisulphide of carbon injected into the soil is of particular value. One ounce injected about 2 ft. from an apple tree on two sides has been found to destroy all the ground form of the woolly aphis. In garden cultivation it is most useful for wireworm, used at the rate of 1 ounce to every 4 sq. yds. It kills all root pests.

In Great Britain the flea beetles (Halticidae) are one of the most serious enemies; one of these, the turnip flea (Phyllotreta nemorum), has in some years, notably 1881, caused more than £500,000 loss in England and Scotland alone by eating the young seedling turnips, cabbage and other Cruciferae. In some years three or four sowings have to be made before a “plant” is produced, enormous loss in labour and cost of seed alone being thus involved. These beetles, characterized by their skipping movements and enlarged hind femora, also attack the hop (Haltica concinna), the vine in America (Graptodera chalybea, Illig.), and numerous other species of plants, being specially harmful to seedlings and young growth. Soaking the seed in strong-smelling substances, such as paraffin and turpentine, has been found efficacious, and in some districts paraffin sprayed over the seedlings has been practised with decided success. This oil generally acts as an excellent preventive of this and other insect attacks.

In all climates fruit and forest trees suffer from weevils or Curculionidae. The plum curculio (Conotrachelus nenuphar, Herbst) in America causes endless harm in plum orchards; curculios in Australia ravage the vines and fruit trees (Orthorrhinus klugii, Schon, and Leptops hopei, Bohm, &c.). In Europe a number of “long-snouted” beetles, such as the raspberry weevils (Otiorhynchus picipes), the apple blossom weevil (Anthonomus pomorum), attack fruit; others, as the “corn weevils” (Calandra oryzae and C. granaria), attack stored rice and corn; while others produce swollen patches on roots (Ceutorhynchus sulcicollis), &c. All these Curculionidae are very timid creatures, falling to the ground at the least shock. This habit can be used as a means of killing them, by placing boards or sacks covered with tar below the trees, which are then gently shaken. As many of these beetles are nocturnal, this trapping should take place at night. Larval “weevils” mostly feed on the roots of plants, but some, such as the nut weevil (Balaninus nucum), live as larvae inside fruit. Seeds of various plants are also attacked by weevils of the family Bruchidae, especially beans and peas. These seed-feeders may be killed in the seeds by subjecting them to the fumes of bisulphide of carbon. The corn weevils (Calandra granaria and C. oryzae) are now found all over the world, in many cases rendering whole cargoes of corn useless.

The most important Hymenopterous pests are the sawflies or Tenthredinidae, which in their larval stage attack almost all vegetation. The larvae of these are usually spoken of as “false caterpillars,” on account of their resemblance to the larvae of a moth. They are most ravenous feeders, stripping bushes and trees completely of their foliage, and even fruit. Sawfly larvae can at once be recognized by the curious positions they assume, and by the number of pro-legs, which exceeds ten. The female lays her eggs in a slit made by means of her “saw-like” ovipositor in the leaf or fruit of a tree. The pupae in most of these pests are found in an earthen cocoon beneath the ground, or in some cases above ground (Lophyrus pini). One species, the slugworm (Eriocampa limacina), is common to Europe and America; the larva is a curious slug-like creature, found on the upper surface of the leaves of the pear and cherry, which secretes a slimy coating from its skin. Currant and gooseberry are also attacked by sawfly larvae (Nematus ribesii and N. ventricosus) both in Europe and America. Other species attack the stalks of grasses and corn (Cephus pygmaeus). Forest trees also suffer from their ravages, especially the conifers (Lophyrus pini). Another group of Hymenoptera occasionally causes much harm in fir plantations, namely, the Siricidae or wood-wasps, whose larvae burrow into the trunks of the trees and thus kill them. For all exposed sawfly larvae hellebore washes are most fatal, but they must not be used over ripe or ripening fruit, as the hellebore is poisonous.

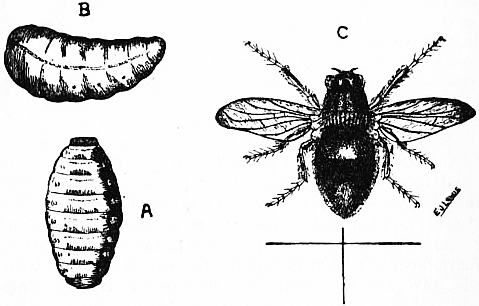

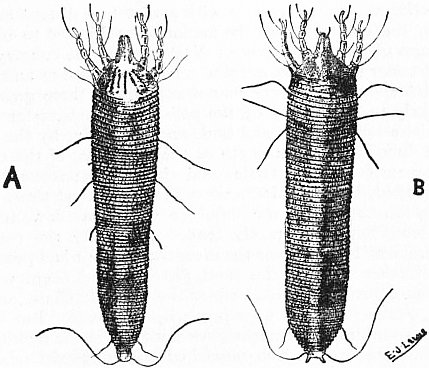

The order Diptera contains a host of serious pests. These two-winged insects attack all kinds of plants, and also animals in their larval stage. Many of the adults are bloodsuckers (Tabanidae, Culicidae, &c.); others are parasitic in their larval stage (Oestridae, &c.). The best-known dipterous pests are the Hessian fly (Cecidomyia destructor), the pear midge (Diplosis pyrivora), the fruit flies (Tephritis Tyroni of Queensland and Halterophora capitata or the Mediterranean fruit fly), the onion fly (Phorbia cepetorum), and numerous corn pests, such as the gout fly (Chloropstaeniopus) and the frit fly (Oscinis frit). Animals suffer from the ravages of bot flies (Oestridae) and gad flies (Tabanidae); while the tsetse disease is due to the tsetse fly (Glossina morsitans), carrying the protozoa that cause the disease from one horse to another. Other flies act as disease-carriers, including the mosquitoes (Anopheles), which not only carry malarial germs, but also form a secondary host for these parasites. Hundreds of acres of wheat are lost annually in America by the ravages of the Hessian fly; the fruit flies of Australia and South Africa cause much loss to orange and citron growers, often making it necessary to cover the trees in muslin tents for protection. Of animal pests the ox warbles (Hypoderma lineata and H. bovis) are the most important (see fig. 2). The “bots” or larvae of these flies live under the skin of cattle, producing large swollen lumps—“warbles”—in which the “bots” mature (fig. 2). These parasites damage the hide, set up inflammation, and cause immense loss to farmers, herdsmen and butchers. The universal attack that has been made upon this pest has, however, largely decreased its numbers. In America cattle suffer much from the horn fly (Haematobia serrata). The dipterous garden pests, such as the onion fly, carrot fly and celery fly, can best be kept in check by the use of paraffin emulsions and the treatment of the soil with gas-lime after the crop is lifted. Cereal pests can only be treated by general cleanliness and good farming, and of course they are largely kept down by the rotation of crops.

|

| Fig. 2.—A, Ox Bot Maggot; B, puparium; C, Ox Warble Fly (Hypoderma bovis). |

|

| Fig. 3.—Looper-larva of Winter Moth (Cheimatobia brumata). |

Lepidopterous enemies are numerous all over the world. Fruit suffers much from the larvae of the Geometridae, the so-called “looper-larvae” or “canker-worms.” Of these geometers the winter moth (Cheimatobia brumata) is one of the chief culprits in Europe (fig. 3). The females in this moth and in others allied to it are wingless. These insects pass the pupal stage in the ground, and reach the boughs to lay their eggs by crawling up the trunks of the trees. To check them, “grease-banding” round the trees has been adopted; but as many other pests eat the leafage, it is best to kill all at once by spraying with arsenical poisons. Among other notable Lepidopterous pests are the “surface larvae” or cutworms (Agrotis spp.), the caterpillars of various Noctuae; the codling moth (Carpocapsa pomonella), which causes the maggot in apples, has now become a universal pest, having spread from Europe to America and to most of the British Colonies. In many years quite half the apple crop is lost in England owing to the larvae destroying the fruit. Sugar-canes suffer from the sugar-cane borer (Diatioca sacchari) in the West Indies; tobacco from the larvae of hawk moths (Sphingidae) in America; corn and grass from various Lepidopterous pests all over the world. Nor are stored goods exempt, for much loss annually takes place in corn and flour from the presence of the larvae of the Mediterranean flour moth (Ephestia kuniella); while furs and clothes are often ruined by the clothes moth (Tinea trapezella).

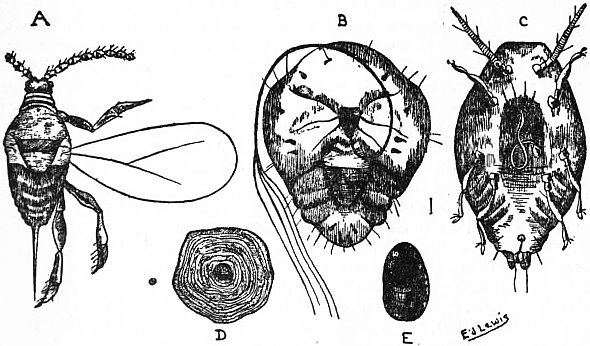

By far the most destructive insects in warm climates belong to the Hemiptera, especially to the Coccidae or scale insects. All fruit and forest trees suffer from these curious insects, which in the female sex always remain apterous and apodal and live attached to the bark, leaf and fruit, hidden beneath variously formed scale-like coverings. The male scales differ in form from the female; the adult male is winged, and is rarely seen. The female lays her eggs beneath the scaly covering, from which hatch out little active six-legged larvae, which wander about and soon begin to form a new scale. The Coccidae can, and mainly do, breed asexually (parthenogenetically). One of the most important is the San José scale (Aspidiotus perniciosus), which in warm climates attacks all fruit and many other trees, which, if unmolested, it will soon kill (fig. 4). These scales breed very rapidly; Howard states one may give rise to a progeny of 3,216,080,400 in one year. Other scale insects of note are the cosmopolitan mussel scale (Mytilaspis pomorum) and the Australian Icerya purchasi. The former attacks apple and pear; the latter, which selects orange and citron, was introduced into America from Australia, and carried ruin before it in some orange districts until its natural enemy, the lady-bird beetle, Vedalia cardinalis, was also imported.

|

| Fig. 4.—San José Scale (Aspidiotus perniciosus). A, Male scale insect; B, female; C, larva; D, female scale; E, male scale. |

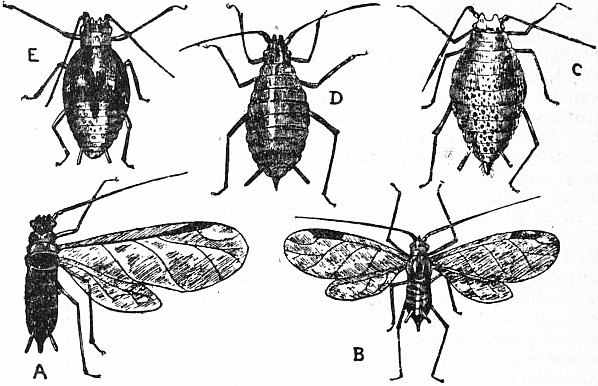

After the Coccidae the next most important insects economically are the plant lice or Aphididae. These breed with great rapidity under favourable conditions: one by the end of the year will be accountable, according to Linnaeus, for the enormous number of a quintillion of its species. Aphides are born, as a rule, alive, and the young soon commence to reproduce again. Their food consists mainly of the sap obtained from the leaves and blossom of plants, but some also live on the roots of plants (Phylloxera vastatrix and Schizoneura lanigera). Aphides often ruin whole crops of fruit, corn, hops, &c., by sucking out the sap, and not only check growth, but may even entail the death of the plant. Reproduction is mainly asexual, the females producing living young without the agency of a male. Males in nearly all species appear once a year, when the last female generation, the ovigerous generation, is fertilized, and a few large ova are produced to carry on the continuity of the species over the winter. Some aphides live only on one species of plant, others on two or more plants. An example of the latter is seen in the hop aphis (Phorodon humuli), which passes the winter and lives on the sloe and damson in the egg stage until the middle of May or later, and then flies off to the hops, where it causes endless harm all the summer (fig. 5); it flies back to the prunes to lay its eggs when the hops are ripe. Another aphis of importance is the woolly aphis (Schizoneura lanigera) of the apple and pear: it secretes tufts of white flocculent wool often to be seen hanging in patches from old apple trees, where the insects live in the rough bark and form cankered growths both above and below ground. Aphides are provided with a mealy skin, which does not allow water to be attached to it, and thus insecticides for destroying them contain soft soap, which fixes the solution to the skin; paraffin is added to corrode the skin, and the soft soap blocks up the breathing pores and so produces asphyxiation.

|

| Fig. 5.—The Hop Aphis (Phorodon humuli). A, Winged female; B, winged male; C, ovigerous wingless female; D, viviparous wingless female from plum; E, pupal stage. |

Amongst Orthoptera we find many noxious insects, notably the locusts, which travel in vast cloud-like armies, clearing the whole country before them of all vegetable life. The most destructive locust is the migratory locust (Locusta migratoria), which causes wholesale destruction in the East. Large pits are dug across the line of advance of these great insect armies to stop them when in the larval or wingless stage, and even huge bonfires are lighted to check their flight when adult. So dense are these “locust clouds” that they sometimes quite darken the air. The commonest and most widely distributed migratory locust is Pachytylus cinerascens. The mole cricket (Gryllotalpa vulgaris) and various cockroaches (Blattidae) are also amongst the pests found in this order.

Of Neuroptera there are but few injurious species, and many, such as the lace wing flies (Hemerobiidae), are beneficial.

The Treatment of Insect Pests.—One of the most important ways of keeping insect pests in check is by “spraying” or “washing.” This method has made great advances in recent years. All the pioneer work has been done in America; in fact, until the South-Eastern Agricultural College undertook the elucidation of this subject, little was known of it in England except by a few growers. The results and history of this essential method of treatment are embodied in Professor Lodemann’s work on the Spraying of Plants, 1896. In this treatment we have to bear in mind what the entomologist teaches us, that is, the nature, habits and structure of the pest.

For insects provided with a biting mouth, which take nourishment from the whole leaf, shoot or fruit, the poisonous washes used are chiefly arsenical. The two most useful arsenical sprays are Paris green and arsenate of lead. To make the former, mix 1 oz. of the Paris green with 15 gallons of soft water, and add 2 oz. of lime and a small quantity of agricultural treacle; the latter is prepared by dissolving 3 oz. of acetate of lead in a little water, then 1 oz. of arsenate of soda in water and mixing the two well together, and adding the whole to 16 gallons of soft water; to this is added a small quantity of coarse treacle. For piercing-mouthed pests like Aphides no wash is of use unless it contains a basis of soft soap. This soft-soap wash kills by contact, and may be prepared in the following way:—Dissolve 6 to 8 ℔ of the best soft soap in boiling soft water and while still hot (but of course taken off the fire) add 1 gallon of paraffin oil and churn well together with a force-pump; the whole may then be mixed with 100 gallons of soft water. The oil readily separates from the water, and thus a perfect emulsion is not obtained: this difficulty has been solved by Mr Cousin’s paraffin naphthalene wash, which is patented, but can be made for private use. It is prepared as follows:—Soft soap, 6 ℔ dissolved in 1 quart of water; naphthalene, 10 oz. mixed with 1½ pint of paraffin; the whole is mixed together. When required for use, 1 ℔ of the compound is dissolved in 5 to 10 gallons of warm water.

These two washes are essential to the well-being of every orchard in all climates. Not only can we now destroy larval and adult insects, but we can also attack them in the egg stage by the use of a caustic alkali wash during the winter; besides destroying the eggs of such pests as the Psyllidae, red spider, and some aphides, this also removes the vegetal encumbrances which shelter numerous other insect pests during the cold part of the year. Caustic alkali wash is prepared by dissolving 1 ℔ of crude potash and 1 ℔ of caustic soda in soft water, mixing the two solutions together, adding to them ¾ ℔ of soft soap, and diluting with 10 gallons of soft water when required for use. Another approved insecticide for scale insects is resin wash, which acts in two ways: first, corroding the soft scales, and second, fixing the harder scales to stop the egress of the hexapod larvae. It is prepared as follows:—First crush 8 ℔ of resin in a sack, and then place the resin in warm water and boil in a cauldron until thoroughly dissolved; then melt 10 ℔ of caustic soda in enough warm water to keep it liquid, and mix with the dissolved resin; keep stirring until the mixture assumes a clear coffee-colour, and for ten minutes afterwards; then add enough warm water to bring the whole up to 25 gallons, and well stir. Bottle this off, and when required for use dilute with three times its bulk of warm soft water, and spray over the trees in the early spring just before the buds burst. For mites (Acari) sulphur is the essential ingredient of a spray. Liver of sulphur has been found to be the best form, especially when mixed with a paraffin emulsion. Bud mites (Phytoptidae, fig. 6) are of course not affected. Sulphur wash is made by adding to every 10 gallons of warm paraffin emulsion or paraffin-naphthalene-emulsion 7 oz. of liver of sulphur, and stirring until the sulphur is well mixed. This is applied as an ordinary spray. Nursery stock should always be treated, to kill scale, aphis and other pests which it may carry, by the gas treatment, particularly in the case of stock imported from a foreign climate. This treatment, both out of doors and under glass, is carried out as follows:—Cover the plants in bulk with a light gas-tight cloth, or put them in a special fumigating house, and then place 1 oz. of cyanide of potassium in lumps in a dish with water beneath the covering, and then pour 1 oz. of sulphuric acid over it (being careful not to inhale the poisonous fumes) for every 1000 cub. ft. of space beneath the cover. The gas generated, prussic acid, should be left to work for at least an hour before the stock is removed, when all forms of animal life will be destroyed.

|

| Fig. 6.—Bud Mites (Phytoptidae). A, Currant Bud Mite (Phytoptus ribis); B, Nut Bud Mite (P. avellanae). |

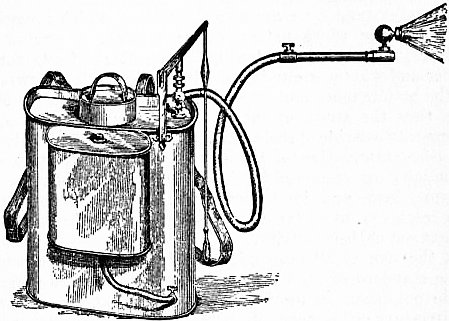

For spraying, proper instruments must be used, by means of which the liquid is sent out over the plants in as fine a mist as possible. Numerous pumps and nozzles are now made by which this end is attained. Both horse and hand machines are employed, the former for hops and large orchards, the latter for bush fruit and gardens. In America, where trees in parks as well as orchards and gardens are treated, steam-power is sometimes used. Among the most important sprayers are the Strawson horse sprayers and the smaller Eclair and Notus knapsack pumps, carried on the back (fig. 7). The nozzles for “mistifying” the wash most in use are known as the Vermorel and Riley’s, which can be fitted to any length of tubing, so as to reach any height, and can be turned in any direction. The pumps in the machine keep the insecticide constantly mixed, and at the same time force the wash with great strength through the nozzle, and so to the exterior, as a fine mist; every part of the plant is thus affected.

|

| Fig. 7.—Knapsack Sprayer for Liquid Insecticides. |

Beneficial Insects have also to be considered in economic entomology. They are of two kinds—(1) those that help to keep down an excess of other insects by acting either as parasites or by being insectivorous in habit; and (2) insects of economic value, such as the bee and silkworm. Amongst the most important friends to the farmer and gardener are the Hymenopterous families of ichneumon flies (Ichneumonidae and Braconidae); the Dipterous families Syrphidae and Tachinidae; the Coleopterous families Coccinellidae and Carabidae; and the Neuropterous Hemerobiidae, or lace-wing flies. Ichneumon flies lay their eggs either in the larvae or ova of other insects, and the parasites destroy their host. In this way the Hessian fly is doubtless kept in check in Europe, and the aphides meet with serious hindrance to their increase. If a number of plant-lice are examined, a few will be found looking like little pearls; these are the dried skins of those that have been killed by Ichneumonidae. The Syrphidae, or hover flies, are almost exclusively aphis-feeders in their larval stage. Tachina flies attack lepidopterous larvae. One of the most notable examples of the use of insect allies is the case of the Australian lady-bird, Vedalia cardinalis, which, in common with all lady-birds, feeds off Aphidae and Coccidae. The Icerya scale (Icerya purchasi) imported into America ruined the orange groves, but its enemy, the Vedalia, was also imported from Australia, and counteracted its abnormal increase with such great results that the crippled orange groves are now once more profitable.