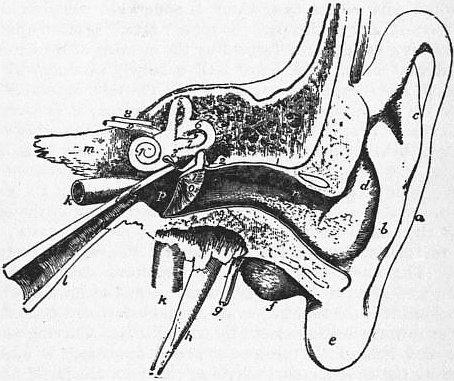

Ear (common Teut.; O.E. éare, Ger. Ohr, Du. oor, akin to Lat. auris, Gr. οὖς), in anatomy, the organ of hearing. The human ear is divided into three parts—external, middle and internal. The external ear consists of the pinna and the external auditory meatus. The pinna is composed of a yellow fibro-cartilaginous framework covered by skin, and has an external and an internal or cranial surface. Round the margin of the external surface in its upper three quarters is a rim called the helix (fig. 1, a), in which is often seen a little prominence known as Darwin’s tubercle, representing the folded-over apex of a prick-eared ancestor. Concentric with the helix and nearer the meatus is the antihelix (c), which, above, divides into two limbs to enclose the triangular fossa of the antihelix. Between the helix and the antihelix is the fossa of the helix. In front of the antihelix is the deep fossa known as the concha (fig. 1, d), and from the anterior part of this the meatus passes inward into the skull. Overlapping the meatus from in front is a flap called the tragus, and below and behind this is another smaller flap, the antitragus. The lower part of the pinna is the lobule (e), which contains no cartilage. On the cranial surface of the pinna elevations correspond to the concha and to the fossae of the helix and antihelix. The pinna can be slightly moved by the anterior, superior and posterior auricular muscles, and in addition to these there are four small intrinsic muscles on the external surface, known as the helicis major and minor, the tragicus and the antitragicus, and two on the internal surface called the obliquus and transversus. The external auditory meatus (fig. 1, n) is a tube running at first forward and upward, then a little backward and then forward and slightly downward; of course all the time it is also running inward until the tympanic membrane is reached. The tube is about an inch long, its outer third being cartilaginous and its inner two-thirds bony. It is lined by skin in its whole length, the sweat glands of which are modified to secrete the wax or cerumen.

|

|

| Fig. 1.—The Ear as seen in Section. | |

a, Helix. b, Antitragus. c, Antihelix. d, Concha. e, Lobule. f, Mastoid process. g, Portio dura. h, Styloid process. k, Internal carotid artery. l, Eustachian tube. |

m, Tip of petrous process. n, External auditory meatus. o, Membrana tympani. p, Tympanum. 1, points to malleus. 2, to incus. 3, to stapes. 4, to cochlea. 5, 6, 7, the three semicircular canals. 8 and 9, facial and auditory nerves. |

The middle ear or tympanum (fig. 1, p) is a small cavity in the temporal bone, the shape of which may perhaps be realized by imagining a hock bottle subjected to lateral pressure in such a way that its circular section becomes triangular, the base of the triangle being above. The neck of the bottle, also laterally compressed, will represent the Eustachian tube (fig. 1, l), which runs forward, inward and downward, to open into the naso-pharynx, and so admits air into the tympanum. The bottom of the bottle will represent the posterior wall of the tympanum, from the upper part of which an opening leads backward into the mastoid antrum and so into the air-cells of the mastoid process. Lower down is a little pyramid which transmits the stapedius muscle, and at the base of this is a small opening known as the iter chordae posterius, for the chorda tympani to come through from the facial nerve. The roof is formed by a very thin plate of bone, called the tegmen tympani, which separates the cavity from the middle fossa of the skull. Below the roof the upper part of the tympanum is somewhat constricted off from the rest, and to this part the term “attic” is often applied. The floor is a mere groove formed by the meeting of the external and internal walls. The outer wall is largely occupied by the tympanic membrane (fig. 1, o), which entirely separates the middle ear from the external auditory meatus; it is circular, and so placed that it slopes from above, downward and inward, and from behind, forward and inward. Externally it is lined by skin, internally by mucous membrane, while between the two is a firm fibrous membrane, convex inward about its centre to form the umbo. Just in front of the membrane on the outer wall is the Glaserian fissure leading to the glenoid cavity, and close to this is the canal of Huguier for the chorda tympani nerve. The inner wall shows a promontory caused by the cochlea and grooved by the tympanic plexus of nerves; above and behind it is the fenestra ovalis, while below and behind the fenestra rotunda is seen, closed by a membrane. Curving round, above and behind the promontory and fenestrae, is a ridge caused by the aqueductus Fallopii or canal for the facial nerve. The whole tympanum is about half an inch from before backward, and half an inch high, and is spanned from side to side by three small bones, of which the malleus (fig. 1, 1) is the most external. This is attached by its handle to the umbo of the tympanic membrane, while its head lies in the attic and articulates posteriorly with the upper part of the next bone or incus (fig. 1, 2). The long process of the incus runs downward and ends in a little knob called the os orbiculare, which is jointed on to the stapes or stirrup bone (fig. 1, 3). The two branches of the stapes are anterior and posterior, while the footplate fits into the fenestra ovalis and is bound to it by a membrane. It will thus be seen that the stapes lies nearly at right angles to the long process of the incus. From the front of the malleus a slender process projects forward into the Glaserian fissure, while from the back of the incus the posterior process is directed backward and is attached to the posterior wall of the tympanum. These two processes form a fulcrum by which the lever action of the malleus and incus is brought about, so that when the handle of the malleus is pushed in by the membrane the head moves out; the top of the incus, attached to it, also moves out, and the os orbiculare moves in, and so the stapes is pressed into the fenestra ovalis. The stapedius and tensor tympanic muscles, the latter of which enters the tympanum in a canal just above the Eustachian tube to be attached to the malleus, modify the movements of the ossicles.

The mucous membrane lining the tympanum is continuous through the Eustachian tube with that of the naso-pharynx, and is reflected on to the ossicles, muscles and chorda tympani nerve. It is ciliated except where it covers the membrana tympani, ossicles and promontory; here it is stratified.

|

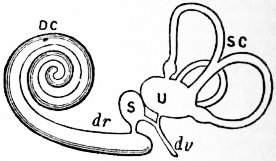

| Fig. 2.—Diagram of the Membranous Labyrinth. |

DC, Ductus cochlearis. dr, Ductus reuniens. S, Sacculus. U, Utriculus. dv, Ductus endolymphaticus. SC, Semicircular canals. (After Waldeyer.) |

The internal ear or labyrinth consists of a bony and a membranous part, the latter of which is contained in the former. The bony labyrinth is composed of the vestibule, the semicircular canals and the cochlea. The vestibule lies just internal to the posterior part of the tympanum, and there would be a communication between the two, through the fenestra ovalis, were it not that the footplate of the stapes blocks the way. The inner wall of the vestibule is separated from the bottom of the internal auditory meatus by a plate of bone pierced by many foramina for branches of the auditory nerve (fig. 1, 9), while at the lower part is the opening of the aqueductus vestibuli, by means of which a communication is established with the posterior cranial fossa. Posteriorly the three semicircular canals open into the vestibule; of these the external (fig. 1, 7) has two independent openings, but the superior and posterior (fig. 1, 5 and 6) join together at one end and so have a common opening, while at their other ends they open separately. The three canals have therefore five openings into the vestibule instead of six. One end of each canal is dilated to form its ampulla. The superior semicircular canal is vertical, and the two pillars of its arch are nearly external and internal; the external canal is horizontal, its two pillars being anterior and posterior, while the convexity of the arch of the posterior canal is backward and its two pillars are superior and inferior. Anteriorly the vestibule leads into the cochlea (fig. 1, 4), which is twisted two and a half times round a central pillar called the modiolus, the whole cochlea forming a rounded cone something like the shell of a snail though it is only about 5 mm. from base to apex. Projecting from the modiolus is a horizontal plate which runs round it from base to apex like a spiral staircase; this is known as the lamina spiralis, and it stretches nearly half-way across the canal of the cochlea. At the summit it ends in a little hook named the hamulus. The modiolus is pierced by canals which transmit branches of the auditory nerve to the lamina spiralis.

|

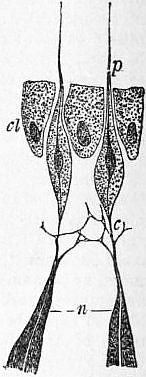

| Fig. 3.—cl, Columnar cells covering the crista acustica; p, peripheral, and c, central processes of auditory cells; n, nerve fibres. (After Rüdinger.) |

The membranous labyrinth lies in the bony labyrinth, but does not fill it; between the two is the fluid called perilymph, while inside the membranous labyrinth is the endolymph. In the bony vestibule lie two membranous bags, the saccule (fig. 2, S) in front, and the utricle (fig. 2, U) behind; each of these has a special patch or macula to which twigs of the auditory nerve are supplied, and in the mucous membrane of which specialized hair cells are found (fig. 3, p).

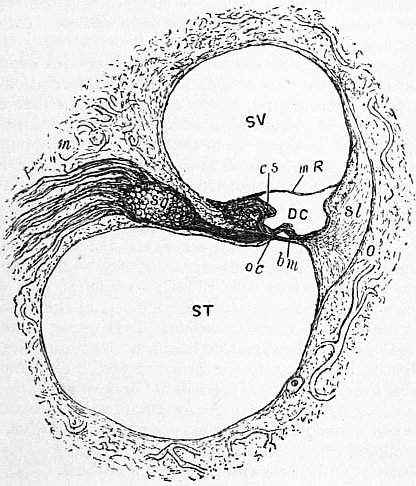

Attached to the maculae are crystals of carbonate of lime called otoconia. The membranous semicircular canals are very much smaller in section than the bony; in the ampulla of each is a ridge, the crista acustica, which is covered by a mucous membrane containing sensory hair cells like those in the maculae. All the canals open into the utricle. From the lower part of the saccule a small canal called the ductus endolymphaticus (fig. 2, dv) runs into the aqueductus vestibuli; it is soon joined by a small duct from the utricle, and ends, close to the dura mater of the posterior fossa of the cranium, as the saccus endolymphaticus, which may have minute perforations through which the endolymph can pass. Anteriorly the saccule communicates with the membranous cochlea or scala media by a short ductus reuniens (fig. 2, dr). A section through each turn of the cochlea shows the bony lamina spiralis, already noticed, which is continued right across the canal by the basilar membrane (fig. 4, bm), thus cutting the canal into an upper and lower half and connected with the outer wall by the strong spiral ligament (fig. 4, sl). Near the free end of the lamina spiralis another membrane called the membrane of Reissner (fig. 4, mR) is attached, and runs outward and upward to the outer wall, taking a triangular slice out of the upper half of the section. There are now three canals seen in section, the upper of which is the scala vestibuli (fig. 4, SV), the middle and outer the scala media, ductus cochlearis or true membranous cochlea (fig. 4, DC), while the lower is the scala tympani (fig. 4, ST). The scala vestibuli and scala tympani communicate at the apex of the cochlea by an opening known as the helicotrema, so that the perilymph can here pass from one canal to the other. At the base of the cochlea the perilymph in the scala vestibuli is continuous with that in the vestibule, but that in the scala tympani bathes the inner surface of the membrane stretched across the fenestra rotunda, and also communicates with the subarachnoid space through the aqueductus cochleae, which opens into the posterior cranial fossa. The scala media containing endolymph communicates, as has been shown, with the saccule through the canalis reuniens, while, at the apex of the cochlea, it ends in a blind extremity of considerable morphological interest called the lagena.

|

|

| Fig. 4.—Transverse Section through the Tube of the Cochlea. | |

m, Modiolus. 0, Outer wall of cochlea. SV, Scala vestibuli. ST, Scala tympani. DC, Ductus cochlearis. mR, Membrane of Reissner. |

bm, Basilar membrane. cs, Crista spiralis. sl, Spiral ligament. sg, Spiral ganglion of auditory nerve. oc, Organ of Corti. |

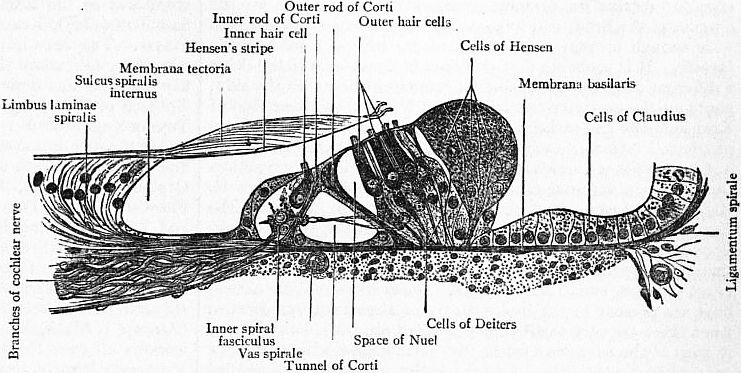

The scala media contains the essential organ of hearing or organ of Corti (fig. 4, oc), which lies upon the inner part of the basilar membrane; it consists of a tunnel bounded on each side of the inner and outer rods of Corti; on each side of these are the inner and outer hair cells, between the latter of which are found the supporting cells of Deiters. Most externally are the large cells of Hensen. A delicate membrane called the lamina reticularis covers the top of all these, and is pierced by the hairs of the hair cells, while above this is the loose membrana tectoria attached to the periosteum of the lamina spiralis, near its tip, internally, and possibly to some of Deiter’s cells externally. The cochlear branch of the auditory nerve enters the lamina spiralis, where a spiral ganglion (fig. 4, sg) is developed on it; after this it is distributed to the inner and outer hair cells.

|

| (From R. Howden—Cunningham’s Text-Book of Anatomy.) |

| Fig. 5.—Transverse Section of Corti’s Organ from the Central Coil of Cochlea (Retzius). |

For further details see Text-Book of Anatomy, edited by D.J. Cunningham (Edinburgh, 1906); Quain’s Elements of Anatomy (London, 1893); Gray’s Anatomy (London, 1905); A Treatise on Anatomy, edited by H. Morris (London, 1902); A Text-Book of Human Anatomy, by A. Macalister (London, 1889).

Embryology.—The pinna is formed from six tubercles which appear round the dorsal end of the hyomandibular cleft or, more strictly speaking, pouch. Those for the tragus and anterior part of the helix belong to the first or mandibular arch, while those for the antitragus, antihelix and lobule come from the second or hyoid arch. The tubercle for the helix is dorsal to the end of the cleft where the two arches join. The external auditory meatus, tympanum and Eustachian tube are remains of the hyomandibular cleft, the membrana tympani being a remnant of the cleft membrane and therefore lined by ectoderm outside and entoderm inside. The origin of the ossicles is very doubtful. H. Gadow’s view, which is one of the latest, is that all three are derived from the hyomandibular plate which connects the dorsal ends of the hyoid and mandibular bars (Anatomischer Anzeiger, Bd. xix., 1901, p. 396). Other papers which should be consulted are those of E. Gaupp, Anatom. Hefte, Ergebnisse, Bd. 8, 1898, p. 991, and J.A. Hammar, Archiv f. mikr. Anat. lix., 1902. These papers will give a clue to the immense literature of the subject. The internal ear first appears as a pit from the cephalic ectoderm, the mouth of which in Man and other mammals closes up, so that a pear-shaped cavity is left. The stalk of the pear which is nearest the point of invagination is called the recessus labyrinthi, and this, after losing its connexion with the surface of the embryo, grows backward toward the posterior cranial fossa and becomes the ductus endolymphaticus. The lower part of the vesicle grows forward and becomes the cochlea, while from the upper part three hollow circular plates grow out, the central parts of which disappear, leaving the margin as the semicircular canals. Subsequently constrictions appear in the vesicle marking off the saccule and utricle. From the surrounding mesoderm the petrous bone is formed by a process of chondrification and ossification.

See W. His, Junr., Archiv f. Anat. und Phys., 1889, supplement, p. 1; also Streeter, Am. Journ. of Anat. vi., 1907.

Comparative Anatomy.—The ectodermal inpushing of the internal ear has probably a common origin with the organs of the lateral line of fish. In the lower forms the ductus endolymphaticus retains its communication with the exterior on the dorsum of the head, and in some Elasmobranchs the opening is wide enough to allow the passage of particles of sand into the saccule. It is probable that this duct is the same which, taking a different direction and losing its communication with the skin, abuts on the posterior cranial fossa of higher forms (see Rudolf Krause, “Die Entwickelung des Aq. vestibuli seu d. Endelymphaticus,” Anat. Anzeiger, Bd. xix., 1901, p. 49). In certain Teleostean fishes the swim bladder forms a secondary communication with the internal ear by means of special ossicles (see G. Ridewood, Journ. Anat. & Phys. vol. xxvi.). Among the Cyclostomata the external semicircular canals are wanting; Petromyzon has the superior and posterior only, while in Myxine these two appear to be fused so that only one is seen. In higher types the three canals are constant. Concretions of carbonate of lime are present in the internal ears of almost all vertebrates; when these are very small they are called otoconia, but when, as in most of the teleostean fishes, they form huge concretions, they are spoken of as otoliths. One shark, Squatina, has sand instead of otoconia (C. Stewart, Journ. Linn. Society, xxix. 409). The utricle, saccule, semicircular canals, ductus endolymphaticus and a short lagena are the only parts of the ear present in fish.

The Amphibia have an important sensory area at the base of the lagena known as the macula acustica basilaris, which is probably the first rudiment of a true cochlea. The ductus endolymphaticus has lost its communication with the skin, but it is frequently prolonged into the skull and along the spinal canal, from which it protrudes, through the intervertebral foramina, bulging into the coelom. This is the case in the common frog (A. Coggi, Anat. Anz. 5. Jahrg., 1890, p. 177). In this class the tympanum and Eustachian tube are first developed; the membrana tympani lies flush with the skin of the side of the head, and the sound-waves are transmitted from it to the internal ear by a single bony rod—the columella.

In the Reptilia the internal ear passes through a great range of development. In the Chelonia and Ophidia the cochlea is as rudimentary as in the Amphibia, but in the higher forms (Crocodilia) there is a lengthened and slightly twisted cochlea, at the end of which the lagena forms a minute terminal appendage. At the same time indications of the scalae tympani and vestibuli appear. As in the Amphibia the ductus endolymphaticus sometimes extends into the cranial cavity and on into other parts of the body. Snakes have no tympanic membrane. In the birds the cochlea resembles that of the crocodiles, but the posterior semicircular canal is above the superior where they join one another. In certain lizards and birds (owls) a small fold of skin represents the first appearance of an external ear. In the monotremes the internal ear is reptilian in its arrangement, but above them the mammals always have a spirally twisted cochlea, the number of turns varying from one and a half in the Cetacea to nearly five in the rodent Coelogenys. The lagena is reduced to a mere vestige. The organ of Corti is peculiar to mammals, and the single columella of the middle ear is replaced by the three ossicles already described in Man (see Alban Doran, “Morphology of the Mammalian Ossicula auditus,” Proc. Linn. Soc., 1876-1877, xiii. 185; also Trans. Linn. Soc. 2nd Ser. Zool. i. 371). In some mammals, especially Carnivora, the middle ear is enlarged to form the tympanic bulla, but the mastoid cells are peculiar to Man.

For further details see G. Retzius, Das Gehörorgan der Wirbelthiere (Stockholm, 1881-1884); Catalogue of the Museum of the R. College of Surgeons—Physiological Series, vol. iii. (London, 1906); R. Wiedersheim’s Vergleichende Anatomie der Wirbeltiere (Jena, 1902).

Diseases of the Ear

Modern scientific aural surgery and medicine (commonly known as Otology) dates from the time of Sir William Wilde of Dublin (1843), whose work marked a great advance in the application of anatomical, physiological and therapeutical knowledge to the study of this organ. Less noticeable contributions to the subject had not long before been made by Saunders (1827), Kramer (1833), Pilcher (1841) and Yearsley (1841). The next important event in the history of otology was the publication of J. Toynbee’s book in 1860 containing his valuable anatomical and pathological observations. Von Tröltsch of Würzburg, following on the lines of Wilde and Toynbee, produced two well-known works in 1861 and 1862, laying the foundation of the study in Germany. In that country and in Austria he was followed by Hermann Schwartze, Politzer, Gruber, Weber-Liel, Rüdinger, Moos and numerous others. France produced Itard, de la Charrière, Menière, Loewenberg and Bonnafont; and Belgium, Charles Delstanche, father and son. In Great Britain the work was carried on by James Hinton (1874), Peter Allen (1871), Patterson Cassells and Sir William Dalby. In America we may count among the early otologists Edward H. Clarke (1858), D.B. St John Roosa, H. Knapp, Clarence J. Blake, Albert H. Buck and Charles Burnett. Other workers all over the world are too numerous to mention.

Various Diseases and Injuries.—Diseases of the ear may affect any of the three divisions, the external, middle or internal ear. The commoner affections of the auricle are eczema, various tumours (simple and malignant), and serous and sebaceous cysts. Haematoma auris (othaematoma), or effusion of blood into the auricle, is often due to injury, but may occur spontaneously, especially in insane persons. The chief diseases of the external auditory canal are as follows:—impacted cerumen (or wax), circumscribed (or furuncular) inflammation, diffuse inflammation, strictures due to inflammatory affections, bony growths, fungi (otomycosis), malignant disease, caries and necrosis, and foreign bodies.

Diseases of the middle ear fall into two categories, suppurative and non-suppurative (i.e. with and without the formation of pus). Suppurative inflammation of the middle ear is either acute or chronic, and is in either case accompanied by perforation of the drum head and discharge from the ear. The chief importance of these affections, in addition to the symptoms of pain, deafness, discharge, &c., is the serious complications which may ensue from their neglect, viz. aural polypi, caries and necrosis of the bone, affections of the mastoid process, including the mastoid antrum, paralysis of the facial nerve, and the still more serious intracranial and vascular infective diseases, such as abscess in the brain (cerebrum or cerebellum), meningitis, with subdural and extradural abscesses, septic thrombosis of the sigmoid and other venous sinuses, and pyaemia. It is owing to the possibility of these complications that life insurance companies usually, and rightly, inquire as to the presence of ear discharge before accepting a life. Patterson Cassells of Glasgow urged this special point as long ago as 1877. Acute suppurative disease of the middle ear is often due to the exanthemata, scarlatina, measles and smallpox, and to bathing and diving. It may also be caused by influenza, diphtheria and pulmonary phthisis.

Non-suppurative disease of the middle ear may be acute or chronic. In the acute form the inflammation is less violent than in the acute suppurative inflammation, and is rarely accompanied by perforation. Chronic non-suppurative inflammation may be divided into the moist form, in which the symptoms are improved by inflation of the tympanum through the Eustachian tube, and the dry form (including sclerosis), which is more intractable and in which this procedure has little or no beneficial effect. Diseases of the internal ear may be primary or secondary to an affection of the tympanum or to intracranial disease.

Injuries to any part of the ear may occur, among the commoner being injuries to the auricle, rupture of the drum head (from explosions, blows on the ear or the introduction of sharp bodies into the ear canal), and injuries from fractured skull. Congenital malformations of the ear are most frequently met with in the auricle and external canal.

Methods of Examination.—The methods of examining the ear are roughly threefold:—(1) Testing the hearing with watch, voice and tuning-fork. The latter is especially used to distinguish between disease of the middle ear (conducting apparatus) and that of the internal ear (perceptive apparatus). Our knowledge of the subject has been brought to its present state by the labours of many observers, notably Weber, Rinne, Schwabach, Lucae and Gellé. (2) Examination of the canal and drum-head with speculum and reflector, introduced by Kramer, Wilde and von Tröltsch. (3) Examination of the drum-cavity through the Eustachian tube by the various methods of inflation.

Symptoms.—The chief symptoms of ear diseases are deafness, noises in the ear (tinnitus aurium), giddiness, pain and discharge. Deafness (or other disturbance of hearing) and noises may occur from disease in almost any part of the ear. Purulent discharge usually comes from the middle ear. Giddiness is more commonly associated with affections of the internal ear.

Treatment.—Ear diseases are treated on ordinary surgical and medical lines, due regard being had to the anatomical and physiological peculiarities of this organ of sense, and especially to its close relationship, on the one hand to the nose and naso-pharynx, and on the other hand to the cranium and its contents. The chief advance in aural surgery in recent years has been in the surgery of the mastoid process and antrum. The pioneers of this work were H. Schwartze of Halle, and Stacke of Erfurt, who have been followed by a host of workers in all parts of the world. This development led to increased attention being paid to the intracranial complications of suppurative ear disease, in the treatment of which great strides have been made in the last few years.

Effects of Diseases of the Nose on the Ear.—The influence of diseases of the nose and naso-pharynx on ear diseases was brought out by Loewenberg of Paris, Voltolini of Breslau, and especially by Wilhelm Meyer of Copenhagen, the discoverer of adenoid vegetations of the naso-pharynx (“adenoids”), who recognized the great importance of this disease and gave an inimitable account of it in the Trans. of the Royal Medical and Chirurgical Society of London, 1870, and the Archiv für Ohrenheilkunde, 1873. Adenoid vegetations, which consist of an abnormal enlargement of Luschka’s tonsil in the vault of the pharynx, frequently give rise to ear disease in children, and, if not attended to, lay the foundation of nasal and ear troubles in after life. They are often associated with enlargement of the faucial tonsils.

Journals.—In 1864 the Archiv für Ohrenheilkunde was started by Politzer and Schwartze, and, in 1867, the Monatsschrift für Ohrenheilkunde (a monthly publication) was founded by Voltolini, Gruber, Weber-Liel and Rüdinger. Appearing first as the Archives of Ophthalmology and Otology, simultaneously in English and German, in 1869, the Archives of Otology became a separate publication under the editorship of Knapp, Moos and Roosa in 1879. Amongst other journals now existing are Annales des maladies de l’oreille et du larynx (Paris), Journal of Laryngology (London), Centralblatt für Ohrenheilkunde (Leipzig), &c.

Societies.—The earliest society formed was the American Otological Society (1868), which held annual meetings and published yearly transactions. Flourishing societies for the study of otology (sometimes combined with laryngology) exist in almost all civilized countries, and they usually publish transactions consisting of original papers and cases. The Otological Society of the United Kingdom was founded in 1900.

International Congresses.—International Otological congresses have been held at intervals of about four years at New York, Milan, Basel, Brussels, Florence, London and Bordeaux (1904). The proceedings of the congresses appear as substantial volumes.

Hospitals.—The earliest record of a public institution for the treatment of ear diseases is a Dispensary for Diseases of the Eye and Ear in London, started by Saunders and Cooper, which existed in 1804; the aural part, however, was soon closed, so that the actual oldest institution appears to be the Royal Ear Hospital, London, which was founded by Curtis in 1816. Four years later there was started the New York Eye and Ear Infirmary. At the present time in every large town of Europe and America ear diseases are treated either in separate departments of general hospitals or in institutions especially devoted to the purpose.

For a history of otology from the earliest times refer to A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Ear, by D.B. St John Roosa, M.D., LL.D. (6th edition, New York, 1885), and for a general account of the present state of otological science to A Text-Book of the Diseases of the Ear for Students and Practitioners, by Professor Dr Adam Politzer, transl. by Milton J. Ballin, Ph.B., M.D., and Clarence J. Heller, M.D. (4th edition, London, 1902).