Delphi (the Pytho of Homer and Herodotus; in Boeotian inscriptions Βελφοί, on coins Δαλφοί), a place in ancient Greece in the territory of Phocis, famous as the seat of the most important temple and oracle of Apollo. It was situated about 6 m. inland from the shores of the Corinthian Gulf, in a rugged and romantic glen, closed on the N. by the steep wall-like under-cliffs of Mount Parnassus known as the Phaedriades or Shining Rocks, on the E. and W. by two minor ridges or spurs, and on the S. by the irregular heights of Mount Cirphis. Between the two mountains the Pleistus flowed from east to west, and opposite the town received the brooklet of the Castalian fountain, which rose in a deep gorge in the centre of the Parnassian cliff. About 7 m. to the north, on the side of Mount Parnassus, was the famous Corycian cave, a large grotto in the limestone rock, which afforded the people of Delphi a refuge during the Persian invasion. It is now called in the district the Sarant’ Aulai or Forty Courts, and is said to be capable of holding 3000 people.

I. The Site.—The site of Delphi was occupied by the modern village of Castri until it was bought by the French government in 1891, and the peasant proprietors expropriated and transferred to the new village of Castri, a little farther to the west. Excavations had been made previously in some parts of the precinct; for example, the portico of the Athenians was laid bare in 1860. The systematic clearing of the site began in the spring of 1892, and it was rapidly cleared of earth by means of a light railway. The plan of the precinct is now easily traced, and with the help of Pausanias many of the buildings have been identified.

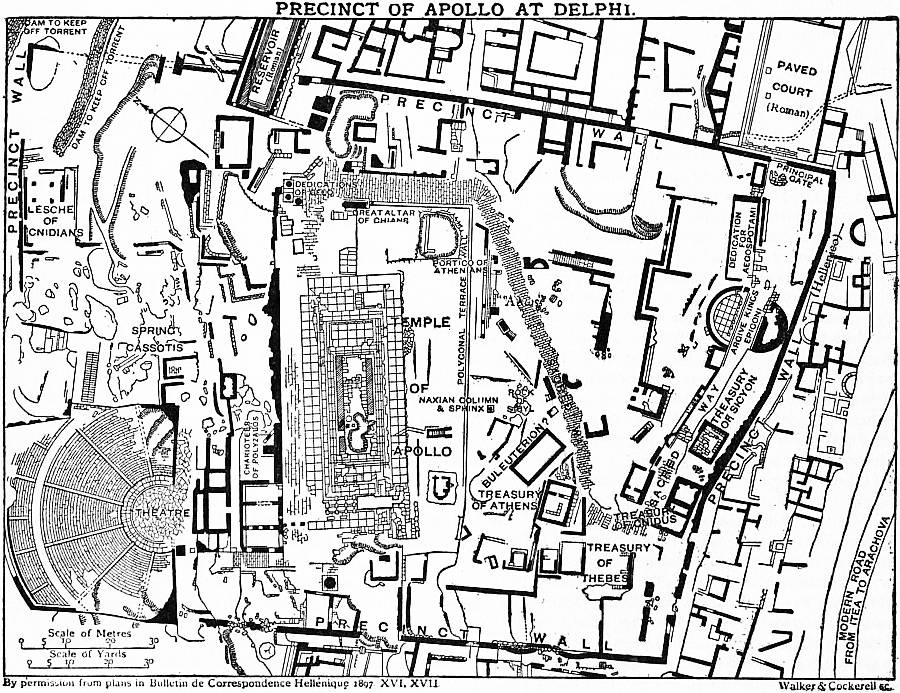

The ancient wall running east and west, commonly known as the Hellenico, has been found extant in its whole length, and the two boundary walls running up the hill at each end of it, traced. In the eastern of these was the main entrance by which Pausanias went in along the Sacred Way. This paved road is easily recognized as it zigzags up the hill, with treasuries and the bases of various offerings facing it on both sides. It mounts first westwards to an open space, then turns eastwards till it reaches the eastern end of the terrace wall that supports the temple, and then turns again and curves up north and then west towards the temple. Above this, approached by a stair, are the Lesche and the theatre, occupying respectively the north-east and north-west corner of the precinct. On a higher level still, a little to the west, is the stadium. There are several narrow paths and stairs that cut off the zigzags of the Sacred Way.

In describing the monuments discovered by the French excavators, the simplest plan is to follow the route of Pausanias. Outside the entrance is a large paved court of Roman date, flanked by a colonnade. On the north side of the Sacred Way, close to the main entrance, stood the offering dedicated by the Lacedaemonians after the battle of Aegospotami. It was a large quadrangular building of conglomerate, with a back wall faced with stucco, and stood open to the road. On a stepped pedestal facing the open stood the statues of the gods and the admirals, perhaps in rows above one another.

The statues of the Epigoni stood on a semicircular basis on the south side of the way. Opposite them stood another semicircular basis which carried the statues of the Argive kings, whose names are cut on the pedestal in archaic characters, reading from right to left. Farther west was the Sicyonian treasury on the south of the way. It was in the form of a small Doric temple in antis, and had its entrance on the east. The present foundations are built of architectural fragments, probably from an earlier building of circular form on the same site. The sculptures from this treasury are in the museum, as are the other sculptures found on the site. These sculptures, which are in rough limestone, most likely belong to the earlier building, as their surface is in a better state of preservation than could be possible if they had been long exposed to the air. The earlier treasury was probably destroyed either by earthquake or by the percolation of water through the terracing.

The Cnidian treasury stands on the south side of the way farther west. This building was originally surmised by the excavators to be the treasury of Siphnos, but further evidence led them to change their opinion. The treasury was raised on a quadrangular structure, supported on its south side by the Hellenico, and built of tufa. The lower courses are left rough and were most likely hidden. A small Ionic temple of marble with two caryatids between antae stood on this substructure. The sculpture from this treasury, which ornamented its frieze and pediment, is of great interest in the history of the development of the art, and the fragments of architectural mouldings are of great delicacy and beauty. The whole work is perhaps the most perfect example we possess of the transitional style of the early 5th century. Standing back somewhat from the path just as it bends round up the hill is the Theban treasury. Farther north, where the path turns again, is the Athenian treasury. This structure, which was in the form of a small Doric temple in antis, appears to have suffered from the building above it having been shaken down by an earthquake. It has now been rebuilt with the original blocks. There can be no doubt about the identity of the building, for the basis on which it stands bears the remains of the dedicatory inscription, stating that it was erected from the spoils of Marathon. Almost all the sculptured metopes are in the museum, and are of the highest interest to the student of archaic art. The famous inscriptions with hymns to Apollo accompanied by musical notation were found on stones belonging to this treasury.

Above the Athenian treasury is an open space, in which is a rock which has been identified as the Sybil’s rock. It has steps hewn in it, and has a cleft. The ground round it has been left rough like the space on the Acropolis at Athens identified as the ancient altar of Athena. Here too was placed the curious column, with many flutes and an Ionic capital, on which stood the colossal sphinx, dedicated by the Naxians, that has been pieced together and placed in the museum.

A little farther on, but below the Sacred Way, is another open space, of circular form, which is perhaps the ἅλως or sacred threshing-floor on which the drama of the slaying of the Python by Apollo was periodically performed. Opposite this space, and backed against the beautifully jointed polygonal wall which has for some time been known, and which supports the terrace on which the temple stands, is the colonnade of the Athenians. A dedicatory inscription runs along the face of the top step, and has been the subject of much dispute. Both the forms of the letters and the style of the architecture show that the colonnade cannot date, as Pausanias says, from the time of the Peloponnesian War; Th. Homolle now assigns it to the end of the 6th century. The polygonal terrace wall at the back, on being cleared, proves to be covered with inscriptions, most of them concerning the manumission of slaves.

After rounding the east end of the terrace wall, the Sacred Way turns northward, leaving the Great Altar, dedicated by the Chians, on the left. After passing the altar, it turns to the left again at right angles, and so enters the space in front of the temple. Remains of offerings found in this region include those dedicated by the Cyrenians and by the Corinthians. The site of the temple itself carries the remains of successive structures. Of that built by the Alcmaeonids in the 6th century B.C. considerable remains have been found, some in the foundations of the later temple and some lying where they were thrown by the earthquake. The sculptures found have been assigned to this building, probably to the gables, as they are archaic in character, and show a remarkable resemblance to the sculptures from the pediment of the early temple of Athena at Athens. The existing foundations are these of the temple built in the 4th century. They give no certain information as to the sacred cleft and other matters relating to the oracle. Though there are great hollow spaces in the structure of the foundations, these appear merely to have been intended to save material, and not to have been put to any religious or other use. Up in the north-eastern corner of the precinct, standing at the foot of the cliffs, are the remains of the interesting Cnidian Lesche or Clubhouse. It was a long narrow building accessible only from the south, and the famous paintings were probably disposed around the walls so as to meet in the middle of the north side. Some scanty fragments of the lower part of the frescoed walls have survived; but they are not enough to give any information as to the work of Polygnotus.

At the north-western corner of the precinct is the theatre, one of the best preserved in Greece. The foundations of the stage are extant, as well as the orchestra, and the walls and seats of the auditorium. There are thirty-three tiers of seats in seven sets, and a paved diazoma. The sculptures from the stage front, now in the museum, have the labours of Heracles as their subject. The date of the theatre is probably early 2nd century B.C.

The stadium lies, as Pausanias says, in the highest part of the city to the north-west. It stands on a narrow plateau of ground supported on the south-east by a terrace wall. The seats have been cleared, and are in a state of extraordinary preservation. A few of those at the east end are hewn in the rock. No trace of the marble seats mentioned by Pausanias has been found, but they have probably been carried off for lime or building, as they could easily be removed. An immense number of inscriptions have been found in the excavations, and many works of art, including a bronze charioteer, which is one of the most admirable statues preserved from ancient times.

II. History.—Our information as to the oracle at Delphi and the manner in which it was consulted is somewhat confused; there probably was considerable variation at different periods. The tale of a hole from which intoxicating “mephitic” vapour arose has no early authority, nor is it scientifically probable (see A. P. Oppé in Journal of Hellenic Studies, xxiv. 214). The questions had to be given in writing, and the responses were uttered by the Pythian priestess, in early times a maiden, later a woman over fifty attired as a maiden. After chewing the sacred bay and drinking of the spring Cassotis, which was conducted into the temple by artificial channels, she took her seat on the sacred tripod in the inner shrine. Her utterances were reduced to verse and edited by the prophets and the “holy men” (ὅσιοι). For the influence and history of the oracle see Oracle.

Delphi also contained the “Omphalos,” a sacred stone bound with fillets, supposed to mark the centre of the earth. It was said Zeus had started two eagles from the opposite extremities and they met there. Other tales said the stone was the one given by Rhea to Cronus as a substitute for Zeus.

For the history of the Delphic Amphictyony see under Amphictyony. The oracle at Delphi was asserted by tradition to have existed before the introduction of the Apolline worship and to have belonged to the goddess Earth (Ge or Gaia). The Homeric Hymn to Apollo evidently combines two different versions, one of the approach of Apollo from the north by land, and the other of the introduction of his votaries from Crete. The earliest stone temple was said to have been built by Trophonius and Agamedes. This was destroyed by fire in 548 B.C., and the contract for rebuilding was undertaken by the exiled Alcmaeonidae from Athens, who generously substituted marble on the eastern front for the poros specified (see Cleisthenes, ad init.). Portions of the pediments of this temple have been found in the excavations; but no sign has been found of the pediments mentioned by Pausanias, representing on the east Apollo and the Muses, and on the west Dionysus and the Thyiades (Bacchantes), and designed by Praxias, the pupil of Calanias. The temple which was seen by Pausanias, and of which the foundations were found by the excavators, was the one of which the building is recorded in inscriptions of the 4th century. A raid on Delphi attempted by the Persians in 480 B.C. was said to have been frustrated by the god himself, by means of a storm or earthquake which hurled rocks down on the invaders; a similar tale is told of the raid of the Gauls in 279 B.C. But the sacrilege thus escaped at the hands of foreign invaders was inflicted by the Phocian defenders of Delphi during the Sacred War, 356-346 B.C., when many of the precious votive offerings were melted down. The Phocians were condemned to replace their value to the amount of 10,000 talents, which they paid in instalments. In 86 B.C. the sanctuary and its treasures were put under contribution by L. Cornelius Sulla for the payment of his soldiers; Nero removed no fewer than 500 bronze statues from the sacred precincts; Constantine the Great enriched his new city by the sacred tripod and its support of intertwined snakes dedicated by the Greek cities after the battle of Plataea. This still exists, with its inscription, in the Hippodrome at Constantinople. Julian afterwards sent Oribasius to restore the temple; but the oracle responded to the emperor’s enthusiasm with nothing but a wail over the glory that had departed.

Provisional accounts of the excavations have appeared during the excavations in the Bulletin de correspondance hellénique. A summary is given in J. G. Frazer, Pausanias, vol. v. The official account is entitled Fouilles de Delphes. For history see Hiller von Gärtringen in Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyclopädie, s.v. “Delphi.” For cult see L. R. Farnell, Cults of the Creek States, iv. 179-218. For the works of art discovered see Greek Art.