Billiards, an indoor game of skill, played on a rectangular table,1 and consisting in the driving of small balls with a stick called a cue either against one another or into pockets according to the methods and rules described below. The name probably originated in the Fr. bille (connected with Eng. “billet”) signifying a stick. Of the origin of the game comparatively little is known—Spain, Italy, France and Germany all being regarded as its original home by various authorities. In an American text-book, Modern Billiards, it is stated that Catkire More (Conn Cetchathach), king of Ireland in the 2nd century, left behind him “fifty-five billiard balls, of brass, with the pools and cues of the same materials.” The same writer refers to the travels of Anacharsis through Greece, 400 B.C., during which he saw a game analogous to billiards. French writers differ as to whether their country can claim its origin, though the name suggests this. While it is generally asserted that Henrique Devigne, an artist, who lived in the reign of Charles IX., gave form and rule to the pastime, the Dictionnaire universel and the Académie des jeux ascribe its invention to the English. Bouillet in the first work says: “Billiards appear to be derived from the game of bowls. It was anciently known in England, where, perhaps, it was invented. It was brought into France by Louis XIV., whose physician recommended this exercise.” In the other work mentioned we read: “It would seem that the game was invented in England.” It was certainly known and played in France in the time of Louis XI. (1423-1483). Strutt, a rather doubtful authority, notwithstanding the reputation attained by his Sports and Pastimes of the People of England, considers it probable that it was the ancient game of Paille-maille (Pall Mall) on a table instead of on the ground or floor—an improvement, he says, “which answered two good purposes: it precluded the necessity of the player to kneel or stoop exceedingly when he struck the bowl, and accommodated the game to the limits of a chamber.” Whatever its origin, and whatever the manner in which it was originally played, it is certain that it was known in the time of Shakespeare, who makes Cleopatra, in the absence of Anthony, invite her attendant to join in the pastime—

|

“Let us to billiards: come, Charmian.” Ant. and Cleo. Act ii. sc. 5. |

In Cotton’s Compleat Gamester, published in 1674, we are told that this “most gentile, cleanly and ingenious game” was first played in Italy, though in another page he mentions Spain as its birthplace. At that date billiards must have been well enough known, for we are told that “for the excellency of the recreation, it is much approved of and played by most nations of Europe, especially in England, there being few towns of note therein which hath not a public billiard table, neither are they wanting in many noble and private families in the country.”

The game was at one time played on a lawn, like modern croquet.1 Some authorities consider that in this form it was introduced into Europe from the Orient by the Crusaders. The ball was rolled or struck with a mallet or cue (with the latter, if Strutt’s allusion to “inconveniences” is correct) through hoops or rings, and these were reproduced for indoor purposes on a billiard-table, as well as a “king” or pin which had to be struck. In the original tables, which were square, there was one pocket, a hole in the centre of the table, as on a bagatelle board, the hoop or ring being retained. Then came similar pockets along one of the side cushions sunk in the bed of the table; and eventually the modern table was evolved, a true oblong or double-square, with pockets opening in the cushions at each corner and in the middle of each long side. The English tables are of this type, small bags of netting being attached to the pockets. The French and American game of billiards is played on a pocketless table. We shall deal first with the English game.

English Billiards

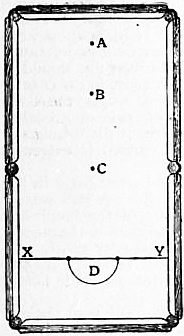

The English table consists of a framework of mahogany or other hard wood, with six legs, and strong enough to bear the weight of five slabs of slate, each 22⁄5 ft. wide by 6 ft. 1½ in., and about 2 in. thick. These having been fitted together with the utmost accuracy to form a level surface, and a green cloth of the finest texture having been tightly strained over it, the cushions are screwed on, and the pockets, for which provision has been made in the slates, are adjusted. As the inside edge of the cushion is not perpendicular to the bed of the table, but is bevelled away so that the top overhangs the base by about ¾ of an in., the actual playing area of the table is 6 ft. wide but is 1½ in. short of 12 ft. long. The height of the table is 2 ft. 8 in. measured from the floor to the cloth. The cloth is in the shape shown in the diagram.

|

A. The billiard spot measured from the nearest point of the face of the cushion. B. Pyramid spot. C. Centre spot. XY. Baulk line. D. Semicircle of 11½ in. radius, known as the D. |

The three spots are on the centre line of the table, and are usually marked by small circular pieces of black tissue paper or court plaster; sometimes they are specially marked for the occasion in chalk. The baulk line and the D are marked either with chalk, tailors’ pipeclay, or an ordinary lead pencil; no other marks appear on the table. Smaller tables provide plenty of practice and amusement, provided that the relation of the length to the breadth be observed. On these tables full-sized balls may be used, the pockets being made slightly smaller than in the full-size table.

In the early part of the 19th century the bed of the table was made of wood, occasionally of marble or stone; green baize was used to cover both the bed and the cushions, the latter made of layers of list. Then as now the cushions proper were glued to a wooden framework which is screwed on to the bed of the table. The old list cushions possessed so little resilience that about 1835 india-rubber was substituted, the value of the improvement being somewhat modified by the fact that in cold weather the rubber became hard and never recovered its elasticity. Vulcanite resisted the cold, but was not “fast” enough, i.e. did not permit the ball to rebound quickly; but eventually a substance was invented, practically proof against cold and sufficiently elastic for all purposes. Late in the 19th century pneumatic cushions were tried, tubes into which air could be pumped, but they did not become popular, though the so-called “ vacuum “cushions give good results. The shape of the face of the cushion has gone through many modifications, owing to the difficulty experienced in the accurate striking of the ball when resting against the cushion with only a small fraction of it’s surface offered to the cue; but low cushions are now made which expose nearly half of the upper part of the ball.

On the size and shape of the pockets depends the ease with which the players score. The mouth of the pocket, known as the “fall” or “drop,” is part of the arc of a circle, the circle being larger in the case of the corner pockets than in that of the middle pockets; the cushions are cut away to admit the passage of the ball. The corner pockets are measured by the length of the tangent drawn at the outside point of the arc to the cushion on either side. The middle pockets are measured at the points where the arc terminates in the cushions. The fall of the middle pockets, i.e. the outside point of the arc, is on the line of the outside face of the cushion; that of the corner pockets is half way down the passage cut in the cushions.

From 1870 to 1885 matches for the championship were played on “Championship Tables,” the pockets measuring only 3 in. at the “fall.” The tables in ordinary use have 35⁄8-in. or 3¾-in. pockets, but in the “Standard Association Tables,” introduced by the Billiard Association at the end of the 19th century, the 35⁄8-in. pocket was adopted for all matches, while the fall of the middle pocket was withdrawn slightly from the cushion-line. Further, as the shape of the shoulders of the cushion at the pockets affects the facility of scoring, the Association adopted a much rounder shoulder than that used in ordinary tables, thereby requiring greater accuracy on the part of the player. In the championship tables the baulk line was only 28 in. from the cushion, and the radius of the D was reduced to 9½ and afterwards to 10 in., the spot being 12½ in. from the top cushion.

The principal games are three in number,—billiards proper, pyramids and pool; and from these spring a variety of others. The object of the player in each game, however, is either to drive one or other of the balls into one or other of the pockets, or (only in billiards proper) to cause the striker’s ball to come into successive contact with two other balls. The former stroke is known as a hazard (a term derived from the fact that the pockets used to be called hazards in old days), the latter as a cannon. When the ball is forced into a pocket the stroke is called a winning hazard; when the striker’s ball falls into a pocket after contact with the object ball, the stroke is a losing hazard; “red hazards” mean that the red ball is the object-ball, “white hazards” the white.

Three balls are used in billiards proper, two white and one red. One of the white balls has a black spot at each end of an imaginary diameter, to distinguish it from the other, the white balls being known as spot-white (or “spot”) and “plain.” They should be theoretically perfect spheres, of identical size and weight, and of equal durability in all parts. The size that is generally used in matches has a diameter of 21⁄16 in., and the weight about 42⁄3 oz. It is exceedingly difficult to get three such ivory balls (the best substance for elasticity) except by cutting up many tusks, and when procured the halls soon lose their perfection, partly because ivory is softer in one part than another, partly because it is very susceptible to changes of weather and temperature, and unequally susceptible in different parts; it is also liable to slight injury in the ordinary course of play. Various substitutes have, therefore, been tried for ivory (q.v.), such as crystalate, or bonzoline (a celluloid compound), and even hollow steel; but their elasticity is inferior to that of ivory, so that the ball rebounds at a wider angle when it strikes. The price of a first-rate set of ivory balls is from four to six guineas; the composition balls cost about half a guinea apiece.

The cue is a rounded rod of seasoned ash about 4 ft. 9 in. in length, tapering from the butt, which is about 1½ in. in diameter, to the tip, which varies in size according to the fancy of the player. The average tip is, however, ½ in. in diameter. The cue weighs generally between 14 and 18 oz. The tip of the cue is usually a leather cap or pad, which, being liable to slip along the surface of the ball in striking, is kept covered with chalk. To the leather tip, the invention of a Frenchman named Mingin (about 1820), and to the control which it gives the player over the ball, the science of modern play is entirely due. The butt of the cue is generally spliced with ebony or some other heavy wood, since a shaft of plain ash is too light for its purpose, and is furthermore liable to warp. At one time it was lawful to use the butt of the cue or even a special instrument with a squared spoon-shaped end called a mace (or mast), in making strokes or giving misses, but now all strokes must be made with the point. The cue is held in one hand, and with the other the player makes a “bridge” by placing wrist and finger-tips on the table, and extending his thumb so as to make a passage along which to slide his cue and to strike the ball. As it is not always possible to reach the ball in this way, longer cues (the “half-butt” and “long butt”) are required; they are used with a “rest,” a shaft of wood at the end of which, perpendicular to the axis, is fastened an × of wood or metal, the cue being rested on the upper half while the lower is on the cloth. A “long rest,” about 6 ft. long, is used with the long cues, the “short rest” (or “jigger”) about 4 ft. long, with the ordinary cue. A marking-board and stands or racks for rests and butts, with iron and brush for the table, and a cover for the table when not in use, complete the billiard “furniture” of the room, apart from its seating accommodation.

The game of billiards proper consists of the making of winning and losing hazards and cannons. It is usually played between two opponents (or four, two against two) for 100 or more points, three being scored for each red hazard, two for each white hazard and two for each cannon. Certain forfeitures on the other hand score to the opponent: running your ball off the table or into a pocket without having hit another ball, 3 (a coup); ordinary misses (not hitting an object-ball), 1. All these forfeits involve the termination of the turn. There are also “foul strokes” which score nothing to the opponent, and only involve the termination of the turn: such as playing with the wrong ball, forcing a ball off the table, hitting a ball twice, &c. When the red ball is pocketed it is replaced on the billiard-spot; if that is occupied, on the pyramid-spot; if that too, on the centre-spot; but if the opponent’s white ball is pocketed it remains out of play till his turn comes. Public matches between adepts are played for higher points, but the rules which govern them are the same. The players have alternate turns, each being “in play” and continuing his “break” until he fails to score.

The game commences by stringing for the lead and choice of balls. The players standing behind the baulk line, strike each a ball from the semicircle up to the top cushion, and he whose ball on its return stops nearest the bottom cushion has the choice of lead and balls. The red ball is placed on the spot at the commencement of the game, and the first player must “break the balls.” The balls are said to be “broken” when the first player has struck the red or given a miss; and the opponent’s ball when off the table is said to be “in hand.” Breaking the balls thus takes place whenever the position, as at the beginning of the game, recurs. The first player (or the player at any stage of the game when he plays after being “in hand”) must place his own ball in any part of the D, or on the lines that form the D, and must play into the part of the table outside the baulk line, for he may not hit direct any ball that is “in baulk,” i.e. on or behind the baulk-line; if he wishes to play at it he must first strike a cushion out of baulk (or, as it is called, bricole). If a player fails to score, the adversary plays, as soon as all the balls are at rest, either from baulk (if “in hand”) or from the place where his own ball has stopped. If by the same stroke a player makes two scores, i.e. a cannon and a hazard for instance, or a winning and a losing hazard, he scores for each of them. Thus if he pockets the red ball and the cue-ball, he scores six, or if he makes a cannon and holes the red ball, five. In the case of a cannon and a losing hazard, made by the same stroke, the value of the hazard depends on the ball first struck. Thus if the cue-ball strikes the red, cannons on to the white, and runs into a pocket, the stroke counts five points, but only one cannon can be made by the same stroke, even if the cue-ball strikes each of the others twice. If both object-balls are struck simultaneously it is considered that the red is struck first. Ten points are the most that can be scored by a single stroke with the cue, namely by striking the red ball first and then the white, and holing all three. If the white ball be struck first and the same series occurs, the value of the stroke is nine points. When the cue-ball and object-ball are touching, whatever the position, the red ball is spotted, the white object-ball put on the centre-spot, and the player plays from baulk.

There are various subtleties in the art of striking, which may be indicated, though only practice can really teach them; the simple stroke being one delivered slightly above the centre of the ball.

The side-stroke is made by striking the object-ball on the side with the point of the cue. The effect of such a mode of striking the ball is to make it travel to the right or to the left, according as it is struck, with a winding or slightly circular motion; and its purpose is to cause the ball to proceed in a direction more or less slanting than is usual, or ordinary, when the ball is struck in or about the centre of its circumference. Many hazards and cannons, quite impossible to be made with the central stroke, are accomplished with ease and certainty by the side-stroke. It was the invention of the leather tip which made side possible. The screw, or twist, is made by striking the ball low down, with a sharp, sudden blow. According as the ball is struck nearer and nearer to the cushion, it stops dead at the point of concussion with the object-ball, or recoils by a series of reverse revolutions, in the manner familiar to the schoolboy in throwing forward a hoop, and causing it to return to his hand by the twist given to its first impetus.

The follow is made by striking the ball high, with a flowing or following motion of the cue. Just as the low stroke impedes the motion of the ball, the follow expedites it.

In the drag the ball is struck low without the sudden jerk of the screw, and with less than the onward push of the follow.

The spot-stroke is a series of winning hazards made by pocketing the red ball in one of the corners from the spot. The great art is, first, to make sure of the hazard, and next, to leave the striking ball in such a position as to enable the player to make a similar stroke in one or other of the corner pockets. To such perfection was the spot-stroke brought, that at the end of the 19th century it was necessary to bar it out of the professional matches, and the “spot-barred” game became consequently the rule for all players. The leading English professionals so completely mastered the difficulties of the stroke and made such long successions of hazards that they practically killed all public interest in billiards, the game being little more than a monotonous series of spot-strokes. In 1888 W.J. Peall made 633 “spots” in succession, and in 1890 in a break of 3304—the longest record—no less than 3183 of the points were scored through spot-stroke breaks. J.G. Sala, by use of the screw-back, made 186 successive hazards in one pocket, but C. Memmott is said to have made as many as 423 such strokes in succession. The spot-stroke was known and used in 1825, when a run of twenty-two “spots” caused quite a sensation. The player, whose name was Carr, offered to play any man in England, but though challenged by Edwin Kentfield never met him, so the latter became champion. Kentfield, however, did not regard the spot-stroke as genuine billiards, rarely played it himself, and had the pocket of his tables reduced to 3 in., and the billiard-spot moved nearer to the top of the table, so as to make the stroke exceedingly difficult. John Roberts, sen., who succeeded Kentfield as champion in 1849, worked hard at the stroke, but never made, in public, a longer run than 104 in succession. But W. Cook, John Roberts, jun., and others, assisted by the improvements made in the implements of the game, soon outdid Roberts, sen., only to be themselves outdone by W. Peall and W. Mitchell, who made such huge breaks by means of the stroke that it was finally barred, the Association rules providing that only two “spots” may be made in succession unless a cannon is combined with a hazard, and that after the second hazard the red ball be placed on the centre-spot.

Top-of-the-Table Play.—When the spot-stroke was dying, many leading players, headed by John Roberts, jun., assiduously cultivated another form of rapid scoring, known as “top-of-the-table-play,” the first principle of which is to collect the three balls at the top of the table near the spot. The balls are then manipulated by means of red winning hazards and cannons, the winning hazard not being made till the object-white can be left close to the spot.

The Push-stroke.—Long series of cannons were also made along the edge of the cushion, mainly by means of the “push-stroke,” and with great rapidity, but eventually the push-stroke too was barred as unfair. It was usually employed when cue-ball and object-ball were very close together and the third ball was in a line, or nearly in a line with them; then by placing the tip of the cue very close to the cue-ball and pushing gently and carefully, not striking, the object-ball could be pushed aside and the cue-ball directed on ball 3.

Balls Jammed in Pockets.—If the two object-balls get jammed, either by accident or design, in the jaws of a corner pocket, an almost interminable series of cannons may be made by a skilful player. T. Taylor made as many as 729 cannons in 1891, but the American champion, Frank C. Ives, in a match with John Roberts, jun., easily beat this in 1893, by making 1267 cannons, before he deliberately broke up the balls. In Ives’s case the balls, however, were just outside the jaws, which were skilfully used to keep the balls close together; but in this game, which was a compromise between English and American billiards, 2¼-in. balls and 3¼-in. pockets were used. Under the aegis of the Billiard Association a tacit understanding was arrived at that the position must be broken up, should it occur. A similar position came into discredit in 1907, in the case of the “cradle-double-kiss” or “anchor” cannon, where the balls were not actually jammed, but so close on each side of a pocket that a long series of cannons could be made without disturbing the position—a stroke introduced by Lovejoy and carried to extremes by him, T. Reece and others (see below).

The Quill or Feather Stroke.—This stroke was barred early in the game’s history. It could only be made when the cue-ball was in hand and the object-ball just outside that part of the baulk-line that helps to form the D. The cue-ball was set so close to the object-ball as only not to touch it, and was then pushed very gently into the pocket, grazing the other so slightly as just to shake it, and no more. A number of similar strokes could thus be made before the object-ball was out of position.

A jenny is a losing hazard into one of the (generally top) pockets when the object-ball is close to the cushion along which the pocket lies: it requires to be played with the side required to turn the ball into the pocket. Long jennies to the top pockets are a difficult and pretty stroke: short jennies are into the middle pockets.

Massé and Piqué.—A massé is a difficult stroke made by striking downwards on the upper surface of the cue-ball, the cue being held nearly at right angles to the table, and the point not being directed towards the centre of the ball. It is generally used to effect a cannon when the three balls are more or less in a line, the cue-ball and the object-ball being close together. The term massé is often used irregularly for piqué, made when the object-ball is as close to the cue-ball as the latter to the cushion, or the third ball, or to make screwing impossible; the cue is then raised to an angle of almost 45° or 50° and its axis directed to the centre of the cue-ball, so that backward rotation is set up. Vignaux, the French player, says, “Le massé est un piqué.” Massé is in fact piqué combined with side.

The perfection of billiards is to be found in the nice combination of the various strokes, in such fashion as to leave the balls in a favourable position after each individual hazard and cannon; and this perfection can only be attained by the most constant and unremitting practice. When the cue-ball is so played that its centre is aimed at the extreme edge of the object-ball, the cue-ball’s course is diverted at what is called the “natural” or “half-ball” angle. If the balls were flat discs instead of spheres the edge of one ball would touch the centre of the other. The object-ball is struck at “three-quarter ball” or “quarter-ball” according as the edge of the cue-ball appears to strike mid-way between the half-ball point and the centre or edge respectively of the object-ball. The half-ball angle is regarded as the standard angle for billiards, other angles being sometimes termed rather vaguely as “rather more or less than half-ball.” The angle of the cue-ball’s new course would be about 45°, were the object-ball fixed, but as the object-ball moves immediately it is struck, the cue-ball is not actually diverted more than 33° from the prolongation of its original course, it being conventional among players to regard the prolongation of the course and not the original track when calculating the angle. The natural angle, and all angles, may be modified by side and screw; the use of strength also makes the ball go off at a wider angle.

Development in Billiard Play.—The modern development of English billiards is due mainly to the skill of such leading players as John Roberts, sen., and his son of the same name. Indeed, their careers form the history of modern billiards from 1849 when the elder Roberts challenged Kentfield (who declined to play) for the championship. No useful comparison can be made between the last-named men, and the change of cushions from list to india-rubber further complicates the question. Kentfield represented the best of the old style of play, and was a most skilful performer; but Roberts had a genius for the game, combined with great nerve and physical power. This capacity for endurance enabled him to practise single strokes till they became certainties, when weaker men would have failed from sheer fatigue; and that process applied to the acquisition of the spot-stroke was what placed him decisively in front of the players of his day until a younger generation taught by him came forward. In 1869 the younger generation had caught him up, and soon afterwards surpassed him at this stroke; both W. Cook and J. Roberts, jun., carried it to greater perfection, but they were in turn put entirely in the shade by W. Mitchell and W.J. Peall. It is curious to realize that John Roberts, sen., developed the game chiefly by means of spot-play, whereas his son continued the process by abandoning it. The public, however, liked quick scoring and long breaks, and therefore a substitute had to be devised. This was provided chiefly by the younger Roberts, whose fertility of resource and manual dexterity eventually placed him by a very long way at the head of his profession. In exhibition matches he barred the spot-stroke and gave his attention chiefly to top-of-the-table play.

The next development was borrowed from the French game (see below), which consists entirely of cannons. Both French and American professors, giving undivided attention to cannons and not being permitted to use the push-stroke, arrived at a perfection in controlling or “nursing” the balls to which English players could not pretend; yet the principles involved in making a long series of cannons were applied, and leading professionals soon acquired the necessary delicacy of touch. The plan is to get the three balls close to each other, say within a space which a hand can cover, and not more than from 4 to 8 in. from a cushion. The striker’s ball should be behind the other two, one of which is nearer the cushion, the other a little farther off and farther forward. The striker’s ball is tapped quietly on the one next the cushion, and hits the third ball so as to drive it an inch or two in a line parallel to the cushion. The ball first struck rebounds from the cushion, and at the close of the stroke all three balls are at rest in a position exactly similar to that at starting, which is called by the French position mère. Thus each stroke is a repetition of the previous one, the positions of the balls being relatively the same, but actually forming a series of short advances along the cushion. With the push-stroke a great number of these cannons could be quickly made, say 50 in 3½ minutes; and, as that means 100 points, scoring was rapid. Most of the great spot-barred breaks contained long series of these cannons, and their value as records is correspondingly diminished, for in such hair’s-breadth distances very often no one but the player, and sometimes not even he, could tell whether a stroke was made or missed or was foul. Push-barred, the cannons are played nearly as fast; but with most men the series is shorter, massé strokes being used when the cannon cannot be directly played.

Championship.—When Kentfield declined to play in 1849, John Roberts, sen., assumed the title, and held the position till 1870, when he was defeated by his pupil W. Cook. The following table gives particulars of championship matches up to 1885:—

| Points. | Date. | Players. | Won by. |

| 1200 | Feb. 11, 1870 | Cook b. Roberts, sen. | 117 |

| 1000 | April 14, 1870 | Roberts, jun., b. Cook | 478 |

| 1000 | May 30, 1870 | Roberts, jun., b. Bowles | 246 |

| 1000 | Nov. 28, 1870 | Jos. Bennett b. Roberts, jun. | 95 |

| 1000 | Jan. 30, 1871 | Roberts, jun., b. Bennett | 363 |

| 1000 | May 25, 1871 | Cook b. Roberts, jun. | 15 |

| 1000 | Nov. 21, 1871 | Cook b. Jos. Bennett | 58 |

| 1000 | March 4, 1872 | Cook b. Roberts, jun. | 201 |

| 1000 | Feb. 4, 1874 | Cook b. Roberts, jun. | 216 |

| 1000 | May 24, 1875 | Roberts, jun., b. Cook | 163 |

| 1000 | Dec. 20, 1875 | Roberts, jun., b. Cook | 135 |

| 1000 | May 28, 1877 | Roberts, jun., b. Cook | 223 |

| 1000 | Nov. 8, 1880 | Jos. Bennett b. Cook | 51 |

| 1000 | Jan. 12, 13, 1881 | Jos. Bennett b. Taylor | 90 |

| 3000 | March 30, 31, and April 1, 1885 | Roberts, jun., b. Cook | 92 |

| 3000 | June 1, 2, 3, 4, 1885 | Roberts, jun., b. Jos. Bennett | 1640 |

These games were played on three-inch-pocket tables, and John Roberts, jun., fairly contended that he remained champion till beaten on such a table under the rules in force when he won the title or under a new code to which he was a consenting party. A match was played for the championship between Roberts and Dawson, in 1899 of 18,000 up, level. The main departure from a championship game lay in the table, which had ordinary, though not easy pockets, instead of three-inch pockets. The match excited much interest, because Dawson, who had already beaten North for the Billiard Association championship, was the first man for many years to play Roberts even; but Roberts secured the game by 1814 points. After this Dawson improved materially, and in 1899, for the second time, he won the Billiard Association championship. His position was challenged by Diggle and Stevenson, who contested a game of 9000 points. Stevenson won by 2900, but lost to Dawson by 2225 points; he beat him in January 1901, and though Dawson won a match before the close of the spring, Stevenson continued to establish his superiority, and at the beginning of 1907 was incontestably the English champion.

Records.—Record scores at billiards have greatly altered since W. Cook’s break of 936, which included 292 spots, and was made in 1873. Big breaks are in some degree a measure of development; but too much weight must not be given to them, for tables vary considerably between easy and difficult ones, and comparisons are apt to mislead. Peall’s break of 3304 (1890) is the largest “all-in” score on record; and in the modern spot-barred and push-barred game with a championship table, H.W. Stevenson in April 1904 made 788 against C. Dawson. In January 1905 John Roberts, however, made 821 in fifty minutes, in a match with J. Duncan, champion of Ireland; but this was not strictly a “record,” since the table had not been measured officially by the Billiard Association. A break of 985 was made by Diggle in 1895 against Roberts, on a “standard table” (before the reduction in size of the pockets). On the 5th of March 1907 T. Reece began beating records by means of the “anchor” stroke, making 1269 (521 cannons), and he made an unfinished 4593 with the same stroke (2268 cannons) on the 23rd of March. Further large breaks followed, including 23,769 by Dawson on the 20th of April 1907, and even more by Reece; and towards the end of the year the Billiard Association ruled the stroke out.

Handicapping.—The obvious way of handicapping unequal players is for the stronger player to allow his opponent an agreed number of points by way of start. Or he may “owe” points, i.e. not begin to reckon his score till he has scored a certain number. A good plan is for the better player to agree to count no breaks that are below a certain figure. The giver of points scores all forfeits for misses, &c. If A can give B 20 points, and B can give C 25 points, the number of points that A can give C is calculated on the following formula,

| 20 + 25 − | 20 × 25 | = 40. |

| 100 |

The handicap of “barring” one or more pockets to the better player, he having only four or five sockets to play into, has been abolished in company with other methods that tended to make the game tedious.

Pyramids is played by two or four persons—in the latter case in sides, two and two. It is played with fifteen balls, placed close together by means of a frame in the form of a triangle or pyramid, with the apex towards the player, and a white striking ball. The centre of the apex ball covers the second or pyramid spot, and the balls forming the pyramid should lie in a compact mass, the base in a straight line with the cushion.

Pyramids is a game entirely of winning hazards, and he who succeeds in pocketing the greatest number of balls wins. Usually the pyramid is made of fifteen red or coloured balls, with the striking ball white. This white ball is common to both players. Having decided on the lead, the first player, placing his ball in the baulk-semicircle, strikes it up to the pyramid, with a view either to lodge a ball in a pocket or to get the white safely back into baulk. Should he fail to pocket a red ball, the other player goes on and strikes the white ball from the place at which it stopped. When either succeeds in making a winning hazard, he plays at any other ball he chooses, and continues his break till he ceases to score; and so the game is continued by alternate breaks until the last red ball is pocketed. The game is commonly played for a stake upon the whole, and a proportionate sum upon each ball or life—as, for instance, 3s. game and 1s. balls. The player wins a life by pocketing a red ball or forcing it over the table; and loses a life by running his own, the white, ball into a pocket, missing the red balls, or intentionally giving a miss. In this game the baulk is no protection; that is to say, the player can pocket any ball wherever it lies, either within or without the baulk line, and whether the white be in hand or not. This liberty is a great and certain advantage under many circumstances, especially in the hands of a good player. It is not a very uncommon occurrence for an adept to pocket six or eight balls in a single break. Both Cook and Roberts have been known, indeed, to pocket the whole fifteen. If four persons play at pyramids, the rotation is decided by chance, and each plays alternately—partners, as in billiards, being allowed to advise each other, each going on and continuing to play as long as he can, and ceasing when he misses a hazard. Foul strokes are reckoned as in billiards, except as regards balls touching each other. If two balls touch, the player proceeds with his game and scores a point for every winning hazard. When all the red balls but one are pocketed, he who made the last hazard plays with the white and his opponent with the red; and so on alternately, till the game terminates by the holing of one or other ball. The pyramid balls are usually a little smaller than the billiard balls; the former are about 2 in. in diameter, the latter 21⁄16 in. to 21⁄8 in.

Losing Pyramids, seldom played, is the reverse of the last-named game, and consists of losing hazards, each player using the same striking ball, and taking a ball from the pyramid for every losing hazard. As in the other game, the baulk is no protection. Another variety of pyramids is known as Shell-out, a game at which any number of persons may play. The pyramid is formed as before, and the company play in rotation. For each winning hazard the striker receives from each player a small stake, and for each losing hazard he pays a like sum, till the game is concluded, by pocketing the white or the last coloured ball.

Pool, a game which may be played by two or more persons, consists entirely of winning hazards. Each player subscribes a certain stake to form the pool, and at starting has three chances or lives. He is then provided with a coloured or numbered ball, and the game commences thus:—The white ball is placed on the spot and the red is played at it from the baulk semicircle. If the player pocket the white he receives the price of a life from the owner of the white; but if he fail, the next player, the yellow, plays on the red; and so on alternately till all have played, or till a ball be pocketed. When a ball is pocketed the striker plays on the ball nearest his own, and goes on playing as long as he can score.

The order of play is usually as follows:—The white ball is spotted; red plays upon white; yellow upon red; then blue, brown, green, black, and spot-white follow in the order of succession named, white playing on spot-white. The order is similar for a larger number, but it is not common for more than seven or eight to join in a pool. The player wins a life for every ball pocketed, and receives the sum agreed on for each life from the owner of that ball. He loses a life to the owner of the ball he plays on and misses; or by making a losing hazard after striking such ball; by playing at the wrong ball, by running a coup; or by forcing his ball over the table. Rules governing the game provide for many other incidents. A ball in baulk may be played at by the striker whose ball is in hand. If the striker’s ball be angled—that is, so placed in the jaws of the pocket as not to allow him to strike the previously-played ball—he may have all the balls except his own and the object ball removed from the table to allow him to try bricole from the cushion. In some clubs and public rooms an angled ball is allowed to be moved an inch or two from the corner; but with a ball so removed the player must not take a life. When the striker loses a life, the next in rotation plays at the ball nearest his own; but if the player’s ball happen to be in hand, he plays at the ball nearest to the centre spot on the baulk line, whether it be in or out of baulk. In such a case the striker can play from any part of the semicircle. Any ball lying in the way of the striker’s ball, and preventing him from taking fair aim and reaching the object-ball, must be removed, and replaced after the stroke. If there be any doubt as to the nearest ball, the distance must be measured by the marker or umpire; and if the distance be equal, the ball to be played upon must be decided by chance. If the striker first pocket the ball he plays on and then runs his own into a pocket, he loses a life to the player whose ball he pocketed, which ball is then to be considered in hand. The first player who loses all his three lives can “star”; that is, by paying into the pool a sum equal to his original stake, he is entitled to as many lives as the lowest number on the marking board. Thus if the lowest number be 2, he stars 2; if 1, he stars 1. Only one star is allowed in a pool; and when there are only two players left in, no star can be purchased. The price of each life must be paid by the player losing it, immediately after the stroke is made; and the stake or pool is finally won by the player who remains longest in the game. In the event, however, of the two players last left in the pool having an equal number of lives, they may either play for the whole or divide the stake. The latter, the usual course, is followed except when the combatants agree to play out the game. When three players are left, each with one life, and the striker makes a miss, the two remaining divide the pool without a stroke—this rule being intended to meet the possible case of two players combining to take advantage of a third. When the striker has to play, he may ask which ball he has to play at, and if being wrongly informed he play at the wrong ball, he does not lose a life. In clubs and public rooms it is usual for the marker to call the order and rotation of play: “Red upon white, and yellow’s your player”; and when a ball has been pocketed the fact is notified—“Brown upon blue, and green’s your player, in hand”; and so on till there are only two or three players left in the pool.

There are some varieties of the game which need brief mention.

Single Pool is the white winning hazard game, played for a stake and so much for each of three or more lives. Each person has a ball, usually white and spot-white. The white is spotted, and the other plays on it from the baulk-semicircle; and then each plays alternately, spotting this ball after making a hazard. For each winning hazard the striker receives a life; for each losing hazard he pays a life; and the taker of the three lives wins the game. No star is allowed in single pool. The rules regulating pool are observed.

Nearest-Ball Pool is played by any number of persons with the ordinary coloured balls, and in the same order of succession. All the rules of pool are followed, except that the baulk is a protection. The white is spotted, and the red plays on it; after that each striker plays upon the ball nearest the upper or outer side of the baulk-line; but if the balls lie within the baulk-line, and the striker’s ball be in hand, he must play up to the top cushion, or place his ball on the spot. If his ball be not in hand, he plays at the nearest ball, wherever it may lie.

Black Pool.—In this game, which lasts for half-an-hour, there are no lives, the player whose ball is pocketed paying the stake to the pocketer. Each player receives a coloured ball and plays in order as in “Following Pool,” the white ball being spotted; there is, in addition, however, a black ball, which is spotted on the centre-spot. When a player has taken a life he may—in some rooms and clubs must—play on the black ball. If he pockets it he receives a stake from each player, paying a stake all round if he misses it, or commits any of the errors for which he would have to pay at “Following Pool.” The black ball cannot be taken in consecutive strokes. Sometimes a pink ball, spotted on the pyramid spot, is added and a single stake is paid all round to the man who pockets it, and a double stake on the black; it is also permitted in some rooms to take blacks and pinks alternately without pocketing a coloured ball between the strokes. Again it is the custom in certain rooms to let a player, after the first round, play on any ball. The game is more amusing when as much freedom is allowed as possible, so that the taking of lives may be frequent. At the end of the half-hour the marker announces at the beginning of the round that it is the last round. White, who lost a stroke at the beginning by being spotted, has the last stroke. If a player wishes to enter the game during its progress his ball is put on the billiard-spot just before white plays, and he takes his first stroke at the end of the round.

Snooker Pool.—This is a game of many and elaborate rules. In principle it is a combination of pyramids and pool. The white ball is the cue-ball for all players. The pyramid balls, set up as in pyramids, count one point each, the yellow ball two points, green ball three, and so on. The black is put on the billiard-spot, the pink on the centre-spot, blue below the apex ball of the pyramid; brown, green and yellow on the diameter of the semicircle, brown on the middle spot, green on the right corner spot of the D, yellow on the left. The players, having decided the order of play, generally by distributing the pool balls from the basket, and playing in the order of colours as shown on the marking board, are obliged to strike a red ball first. If it is pocketed, the player scores one and is at liberty to play on any of the coloured balls; though in some clubs he is compelled to play on the yellow. If he pockets a coloured ball he scores the number of points which that ball is worth, and plays again on a red ball, the coloured ball being replaced on its spot, and so on; but a red ball must always be pocketed before a more valuable ball can be played at. When all the red balls have been pocketed—none are put back on the table as at pyramids—the remaining balls must be pocketed in the pool order and are not replaced. The penalties for missing a ball, running into a pocket, &c., are deducted from the player’s score; they correspond to the values of the balls, one point if the red be missed, two if the yellow be missed, &c. If, before hitting the proper ball, the player hits one of a higher value, the value of that ball is deducted from his score, but there is no further penalty. A player is “snookered” if his ball is so placed that he cannot hit a ball on which he is compelled to play. In this case he is allowed in some rooms to give a miss, but in such a way that the next player is not snookered; in others he must make a bona fide attempt to hit the proper ball off the cushion, being liable to the usual penalty if in so doing he hits a ball of higher value. In some rooms it is considered fair and part of the game to snooker an opponent deliberately; in others the practice is condemned. The rules are so variable in different places that even the printed rules are not of much value, owing to local by-laws.

Among other games of minor importance, being played in a less serious spirit than those mentioned, are Selling Pool, Nearest Ball Pool, Cork Pool and Skittle Pool. The directions for playing them may be found in Billiards (Badminton Library series).

French and American Billiards.—French and American billiards is played on a pocketless table, the only kind of table that is used in France, though the English table with six pockets is also occasionally to be found in America. For match purposes the table used measures 10 ft. by 5 ft., but in private houses and clubs 9 ft. by 4¼ ft. is the usual size, while tables 8 ft. by 4 ft. are not uncommon. The balls, three in number as in English billiards, measure from 2¼ to 23⁄8 in., the latter being “match” size. Since they are both larger and heavier than the English balls, the cues are somewhat heavier and more powerful, so that better effects can be produced by means of “side,” masses, &c. Only cannons (called in America “caroms,” in French caramboles) are played, each counting one point.

The three-ball carom game is the recognized form of American billiards. The table is marked with a centre-spot, “red” spot and “white” spot. The first is on the centre of an imaginary line dividing the table longitudinally into halves; the red (for the red ball) and white spots are on the same line, half-way between the centre-spot and the end cushions, the white spot being on the string-line (corresponding to the English baulk-line). The right to play first is decided, as in England, by “stringing.” The opponent’s white ball and the red ball being spotted, the player plays from within the imaginary baulk-line. Each carom counts one point; a miss counts one to the opponent. A ball is re-spotted on its proper spot if it has been forced off the table. Should red be forced off the table and the red spot be occupied, it is placed on the white spot. White under similar conditions is set on the red spot. The centre spot is only used when, a ball having been forced off the table, both spots are occupied. If a carom be made, and the ball afterwards jumps off the table, it is spotted and the count allowed. If the striker moves a ball not his own before he strikes, he cannot count but may play for safety. If he does so after making a carom the carom does not count, he forfeits one, and his break is ended. If he touches his own ball before he plays, he forfeits a point, and cannot play the stroke. Should he, however, touch his ball a second time, the opponent has the option of having the balls replaced as exactly as possible, or of playing on them as they are left. It is a foul stroke to play with the wrong ball, but if the offence is not detected before a second stroke has been made, the player may continue.

Such long runs of caroms, chiefly “on the rail” along the cushion, have been made by professional players (H. Kerkau, the German champion, making 7156 caroms in 1901 at Zürich), that various schemes have been devised to make the game more difficult. One of these is known as the “continuous baulk-line.” Lines are drawn, 8, 14, 18 or even 22 in. from the rails, parallel to the side of the table, forming with them eight compartments. Of these 14 and 18 are the most general. Only one, two or three caroms, as previously arranged, are allowed to be made in every space, unless one at least of the object-balls is driven over a line. In the space left in the middle of the table any number of caroms may be made without restriction. In the case of the Triangular Baulk-line, lines are drawn at the four corners from the second “sight” on the side-rails to the first sight on the end-rails, forming four triangles within which only a limited number of caroms may be made, unless one object-ball at least be driven outside one of the lines. The Anchor Baulk-lines were devised to checkmate the “anchor” shot, which consisted in getting the object-balls on the rail, one on either side of a baulk-line, and delicately manipulating them so as to make long series of caroms; each ball being in a different compartment, neither had to be driven over a line. The “anchor baulk-lines” form a tiny compartment, 6 in. by 3, and are drawn at the end of a baulk-line where it touches the rail and so divides the compartment into two squares. Only one shot is allowed in this “anchor-space,” unless a ball be driven out of it. By these methods, “crotching” (getting them jammed in a corner) the balls, and long series of rail-caroms were abolished. The push-stroke is strictly forbidden.

The Cushion Carom game is a variety of the ordinary three-ball game, in which no carom counts unless the cue-ball touches a cushion before the carom is completed. There is also Three-Cushion Carom, which is explained by its title, and the Bank-Shot game, in which the cue-ball must touch a cushion before it strikes either ball. The cushion carom games are often used in handicapping, other methods of which are for the better player to make a certain number of caroms “or no count,” and for the weaker to receive a number of points in the game.

In France billiards was played exclusively by the aristocracy and the richer middle class until the first part of the 17th century, when the privilege of keeping billiard-rooms was accorded to the billardiers paulmiers, and billiards became the principal betting game and remained so until the time of Louis Philippe. The most prominent French player of late years is Maurice Vignaux. The French game became the accepted one in the United States about 1870, and the best American players have proved themselves superior to the French masters with the exception of Vignaux. The best-known American masters have been M. Daly, Shaafer, Slosson, Carter, Sexton and Frank C. Ives, doubtless the most brilliant player who ever lived. His record for the 18-in. baulk-line game was an average of 50, with a high run of 290 points. In cushion-caroms he scored a run of 85.

The four-ball game, the original form of American billiards, is practically obsolete. It was formerly played on an English six-pocket table, with a dark-red and a light-red ball and two white ones. At present when played an ordinary table is used, the rules being identical with those of the three-ball game.

Pool is played in America on a six-pocket table with fifteen balls, each bearing a number. There are several varieties of the game, the most popular being Continuous Pool, an expanded form of Fifteen-Ball Pool, in which the balls are set up as in English pyramids, the game being won by the player pocketing the majority of the fifteen balls, each ball counting one point, the numbers being used only to distinguish them, as a player must always name, or “call,” the ball he intends to pocket and the pocket into which he will drive it. The player who “breaks” (plays first) must send at least two balls to the cushion or forfeit three points. The usual method is to strike a corner ball just hard enough to do this but not hard enough to break up the balls, as in that case the second player would have too great an advantage. Balls pocketed by chance in the same play in which a called ball has been legitimately put down are counted; all others pocketed by accident are replaced on the table. In Fifteen-Ball Pool each frame (fifteen balls) constitutes a game. In Continuous Pool the game is for a series of points, generally 100, the balls being set up again after each frame and the player pocketing the last ball having the choice whether to break or cause his opponent to do so.

The balls in Fifteen-Ball Pool are generally all of one colour, usually red. In Pyramid Pool they are parti-coloured as well as numbered, and the game, which usually consists of a single frame, is won by the player who, when all fifteen balls have been pocketed, has scored the greatest aggregate of the numbers on the balls. In Chicago Pool each frame constitutes a game and is won by the player scoring the highest aggregate of numbers on the balls, which are set up round the cushion opposite the diamond sights, the 1 being placed in the middle of the top cushion, opposite the player, with the odd-numbered balls on the player’s left and those with even numbers on his right. The arrangement of the balls, however, varies and is not important. Each player must strike the lowest-numbered ball still on the table, forfeiting the number of points represented by the ball should his ball first hit any other ball, or should he pocket his own ball. If he pockets the proper ball all others that fall into pockets on that play count for him also. Missing the ball played at forfeits three points (sometimes the number on the ball played at), as well as fouls of all kinds. Bottle Pool is played with a cue-ball, the 1 and 2 pool-balls and the leather pool-bottle, which is stood upon its mouth in the middle of the table. A carom on two balls counts 2 points; pocketing the 1-ball counts 1; pocketing the 2-ball counts 2; upsetting bottle from carom counts 5; upsetting bottle to standing position counts 10, or, in many clubs, the game is won when this occurs. Otherwise the game is for 31 points, which number must be scored exactly, a player scoring more than that number being “burst,” and having to begin over again. There are many penalties of one point, such as missing the object-ball, foul strokes, forcing a ball or the bottle off the table, pocketing one’s own ball and upsetting the bottle without hitting a ball. The game of Thirty-Four is played without a bottle, the scoring being by caroms or pocketing the two object-balls. Exactly 34 must be scored or the player is “burst.”

High-Low-Jack-Game is played with a set of pyramid balls by any number of players, the order of starting being determined by distributing the small balls from the pool-bottle. The 15-ball is High, the 1 Low, the 9 Jack, and the highest aggregate of numbers is the game, each of these four counting one point, the game consisting of seven points, and therefore lasting at least for two frames. The balls are set up with the three counting balls in the centre and broken as in pyramids, although balls accidentally falling into pockets count for the player, on which account the balls are sometimes broken as violently as possible. When two or more players have the same score the High ball wins before the Low, &c., as in the card game of the same title.

Pin Pool is played with two white balls, one red and five small pins set up in diamond form in the centre of the table with the pin counting 5 (the king-pin) in the middle, the pins being 3 in. apart. Each player is given a small ball from the bottle and this he keeps secret until he is able to announce that his points, added to the number on his small ball, amount to exactly 31. If he “bursts” he must begin again. Points are made only by knocking down pins, which are numbered 1 to 5. Should a player knock down with one stroke all four outside pins, leaving the 5-pin-standing, it is a “natural” and he wins the game.

Besides these common varieties of pool there are many others which are played in different parts of America, many of them local in character.

Bibliography.—The scientific features of billiards have been discussed at more or less length in several of the following older works:—E. White, Practical Treatise on the Game of Billiards (1807), this was partly a translation of a French treatise, published in 1805, and partly a compilation from the article in the Académie universelle des jeux, issued in the same year, and since frequently re-edited and reprinted; Le Musée des jeux (Paris, 1820); Monsieur Mingaud, The Noble Game of Billiards (Paris, 1834); a translation of the same, by John Thurston (London, 1835); Kentfield, On Billiards (London, 1839), founded principally on the foregoing works: Edward Russell Mardon, Billiards, Game 500 up (London, 1849); Turner, On Billiards, a series of diagrams with instructions (Nottingham, 1849); Captain Crawley, The Billiard Book (London, 1866-1875); Roberts, On Billiards (1868); Fred. Hardy, Practical Billiards, edited by W. Dufton (1867); Joseph Bennett (ex-champion), Billiards (1873). These older books, however, are largely superseded by such modern authorities as the following:—J. Roberts, The Game of Billiards (London, 1898); W. Cook, Billiards (Burroughes & Watts); J.P. Buchanan, Hints on Billiards (Bell & Sons); Modern Billiards (The Brunswick—Balke—Collender Co., New York); Broadfoot, Billiards, Badminton Library (Longmans); Locock, Side and Screw (Longmans); M. Vignaux, Le Billiard (Paris, 1889); A. Howard Cady, Billiards and Pool (Spalding’s Home Library, New York); Thatcher, Championship Billiards, Old and New (Chicago, 1898). For those interested in the purely mathematical aspect of the game, Hemming, Billiards Mathematically Treated, (Macmillan).

1 In 1907 an oval table was introduced in England by way of a change, but this variety is not here considered.

2 A later form of “lawn-billiards” again enjoyed a brief popularity during the latter half of the 19th century. It was played on a lawn, in the centre of which was a metal ring about 5½ in. in diameter, planted upright in such a manner as to turn freely on its axis on a level with the ground. The players, two or more, were provided with implements resembling cues about 4 ft. long and ending in wire loops somewhat smaller in diameter than the wooden balls (one for each player), which were of such a size as barely to pass through the ring. In modern times such games as billiards have afforded scope for various imitations and modifications of this sort.